Children of the Night: Robert E. Howard's Professor John Kirowan & John Conrad

The Arbo Files

Although its origins predate the halcyon age of the pulp magazines, the occult detective figure is without question one of the premiere archetypes of the pulp era. Weird Tales regularly featured the exploits of Jules de Grandin, a former French special agent and master of the occult. Seabury Quinn’s de Grandin stories were more often than not the most popular stories in Weird Tales, outperforming more critically-acclaimed tales by H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard.

Speaking of Howard, his letter exchanges between Lovecraft and others make it clear that he was no fan of the detective fiction genre. Gumshoes and gun molls did little to excite the Texan. Given this, one could assume that the occult detective genre would therefore hold little interest for Howard. After all, an occult detective still detects, and there is always some kind of mystery at the heart of such tales. Howard surprisingly produced his own occult detective stories between 1931 and 1937 (later unpublished stories and drafts would see the light of day between 1967 and 1986). In these tales, two men—Professor John Kirowan and John Conrad—experience high weirdness including supernatural murder, devil worship, and ancestral memory. Although nowhere near as popular nor aesthetically pleasing as either the Conan or Solomon Kane stories, the Kirowan and Conrad tales are nevertheless worthy of reading. They are Howard creations, after all, and that man rarely missed.

The first Kirowan and Conrad story does not primarily focus on either man. Published in the April-May 1931 edition of Weird Tales, “The Children of the Night” is a unique yarn that mostly takes place in the mind of the narrator, John O’Donnel. In the story, O’Donnel, Kirowan, Conrad, Taverel, Clemants, and a certain Ketrick entertain themselves with discussions about race and evolution. Such talk would get each of these men cancelled today, especially those among them who were scholars and literary publishers (Kirowan and Clemants). See, for instance, O’Donnel’s blunt summation of why he felt an instinctual unease around Ketrick.

And let me speak of Ketrick. Each of the six of us was of the same breed —that is to say, a Briton or an American of British descent. By British, I include all natural inhabitants of the British Isles. We represented various strains of English and Celtic blood, but basically, these strains are the same after all. But Ketrick: to me the man always seemed strangely alien. It was in his eyes that this difference showed externally. They were a sort of amber, almost yellow, and slightly oblique. At times, when one looked at his face from certain angles, they seemed to slant like a Chinaman’s.

Elsewhere, the men speak about skull shapes and primordial migrations. In 1931, a conversation between learned gentlemen that touched on eugenics and ethnic differences would not be overly controversial. “The Children of the Night” shows Howard’s familiarity with the works of authors like Franz Boaz and Madison Grant. It also displays an interest in the works of Margaret Murray, an English Egyptologist whose theories similarly influenced Lovecraft. Murray’s most famous work, 1921’s Witch Cult in Western Europe, took the novel position that the great witch hunts that plagued Europe and North America between the 15th and 17th centuries had some basis in fact and practice. Murray theorized that an ancient pagan culture in Europe was uncovered by Reformation and Counter-Reformation officials during their attempts to standardize Christian practices across the Continent. Such a belief was later echoed by the Italian Marxist historian Carlo Ginzburg, albeit without Murray’s most shocking claim—that the witches of Early Modern Europe were in truth biological throwbacks (Neanderthals and Cro-Magnon peoples) confined to the most remote recesses of the countryside.

Howard takes up Murray’s thesis in “The Children of the Night,” as an accidental blow to O’Donnel’s head causes him to remember his previous life as the Celtic warrior, Aryara. In his visions, O’Donnel sees himself as a tall, blond, and blue-eyed warrior fighting his way through the mists of prehistoric Scotland. He describes his enemies as the short, dark, and visibly loathsome first settlers of the land who even predated the Picts. These people are the Children of the Night, a hated race that dwelt in low stone huts and who spoke in patterns reminiscent of lizards. O’Donnel says that the Children of the Night provided the origins of all manner of blasphemous legends within the Celtic tradition, from goblins to various elemental spirits. He hates them totally, and when he comes out of his minor stupor, he recognizes Ketrick as one of their brood. Given its mixture of horror, history, and anthropological content, I for one am convinced that “The Children of the Night” influenced Michael Crichton’s Eaters of the Dead, a 1976 novel about a Muslim official forced into sailing with a Viking band during their war against a strange and savage tribe. The Eaters of the Dead would later be filmed as The 13th Warrior (1999), thus further popularizing themes first articulated in fiction by Howard.

The next Kirowan and Conrad tale, 1934’s “The Haunter of the Ring,” is the first to prominently feature Kirowan and Conrad as the chief protagonists. (“The Thing on the Roof” from 1932 is often cited as a Kirowan and Conrad tale, but neither is named in it.) This, the most famous and anthologized Kirowan and Conrad tale, concerns the misfortune of Evelyn Gordon. According to her husband James, Evelyn tried to murder him on three different occasions, and each time she awoke with no memory of the incidents. The case intrigues Kirowan, who zeroes in on Evelyn’s strange copper ring. The ring, which was given to her by a failed suitor named Joseph Roelocke, features a snake coiled three times with its tail in its mouth. Also, heightening the strangeness of the ring are its eyes, which are encrusted with odd yellow jewels. Kirowan deciphers the ring as being Hungarian in origin, which puts him on the trail of the infamous magician, Yosef Vrolok. Vrolok, an ancestral enemy of Kirowan, gave Evelyn the ring in order to punish her with the ring’s inhabitant—an evil entity related to the god Thoth-amon.

“But I did not need a slip of your tongue to recognize your handiwork. I knew as soon as I saw the ring on Evelyn Gordon's finger; the ring she could not remove; the ancient and accursed ring of Thoth-amon, handed down by foul cults of sorcerers since the days of forgotten Stygia, I knew that ring was yours, and I knew by what ghastly rites you came to possess it. And I knew its power. Once she put it on her finger, in her innocence and ignorance, she was in your power. By your black magic you summoned the black elemental spirit, the haunter of the ring, out of the gulfs of Night and the ages. Here in your accursed chamber you performed unspeakable rituals to drive Evelyn Gordon's soul from her body, and to cause that body to be possessed by that godless sprite from outside the human universe.”

Kirowan manages to break the ring’s spell and send the spirit after Vrolok’s blackened soul. “The Haunter of the Ring” is a quintessential occult detective story worthy of discussion with the tales penned by Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, and Sax Rohmer.

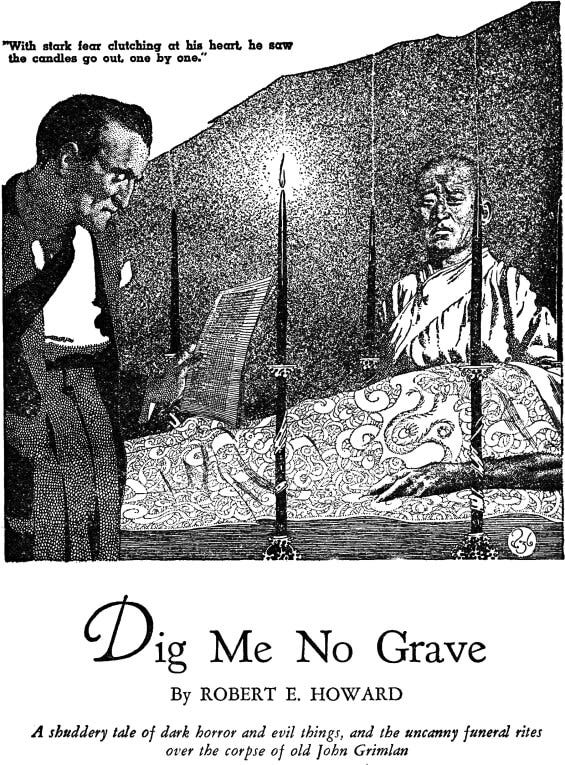

The final Kirowan and Conrad story that we know for certain that Howard finished appeared in Weird Tales several months after Howard’s suicide. First published in February 1937, “Dig Me No Grave” sees Kirowan and Conrad investigating the mysterious death of the miserly hermit, John Grimlan. Hours after Grimlan’s death, Kirowan and Conrad unseal a letter that the late occultist entrusted to Conrad. Despite Grimlan’s wishes that the envelope and its contents be destroyed, Conrad opens it and discovers a horrible secret. Grimlan, who suffered from seizures reminiscent of the ones that plagued the demonically possessed throughout history, was in truth an ageless magician who sold his soul to Menlik Tous in the 17th century!

“What!" I cried, shaken to my soul. “Conrad, this is madness heaped on madness! Malik Tous—good God! No mortal man was ever so named! That is the title of the foul god worshipped by the mysterious Yezidees—they of Mount Alamout the Accursed—whose Eight Brazen Towers rise in the mysterious wastes of deep Asia. His idolatrous symbol is the brazen peacock. And the Muhammadans, who hate his demon-worshipping devotees, say he is the essence of the evil of all the universes—the Prince of Darkness—Ahriman—the old Serpent—the veritable Satan! And you say Grimlan names this mythical demon in his will?”

Howard’s conflation of Melek Taûs, one of the chief deities of the Yezidi religion, with Satan is something that continues to occur in the Middle East to this day. In fact, during their takeover of Iraq in 2014, ISIS fighters singled out the Yezidis for genocide, torture, rape, and mutilation because of the popular Islamic belief that Yezidis are devil worshippers. In “Dig Me No Grave,” which makes other grand religious statements, such as connecting Japanese Shintoism with black magick, Kirowan and Conrad come face-to-face with a spirit of Menlik Tous, who attempts to guard the vile soul of Grimlan. As in “The Haunter of the Ring,” Kirowan’s magic proves stronger, and the deity and the corpse are both defeated in their own way.

The incredibly productive, yet tragically short life of Robert E. Howard saw him write across multiple genres. Some of this work Howard enjoyed more than others, and readers too often overlook or outright refuse to read such things as Howard’s comical or Western tales. The Kirowan and Conrad occult detective stories should not be missed, even despite their relatively low reputation. Not only do these stories touch on and include what would become known as the Cthulhu Mythos, but they also include fascinating tidbits of history, speculative anthropology and archaeology, and actual occult practices. More importantly, they show Howard at the peak of his powers as a two-fisted wordsmith capable of churning out one great story after another. Now that the nights are getting darker, and the world is getter colder, the Kirowan and Conrad stories, which can be consumed in a single sitting, are the perfect accompaniment.

That’s funny, I heard this “Children of the Night” on audiobook yesterday while walking to the library.

I never realized how poetic Howard’s writing was until recently and I’m planning on writing a short story in his style soon. You would never expect this from the inventor of a barbarian character, in stories with so much violence, but he portrays things in such a beautiful way - and then you find his poetry. It’s all so marvellous