For the King or for Richelieu?--that question had to be answered at one time or another by every young 17th Century Frenchman.

But ill-advised political poetry might force that question, as Comte Guy d'Entreville soon discovers. For Cardinal Richelieu himself signed the papers sending Guy's love, Catherine, to a convent for smuggling subversive papers.

Allegedly. If one believes the Cardinal's judges.

Richelieu proposes an exchange: Catherine's freedom for the comte's service in the Cardinal's Guards. Guy asks for a day to consider, as he has been a sworn opponent to the Cardinal. The night that follows will test Guy's resolve as his old friends plot to kill the only man able to secure Catherine's release:

Cardinal Richelieu.

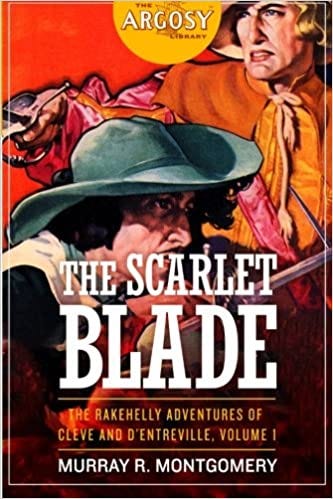

"A Sword for the Cardinal" is the first of six adventures of Guy d'Entrevillle and Richard Cleve by Murry Richardson Montgomery for Argosy. Montgomery is a bit of a mystery. Save for "The Means" in a December 1938 issue of Liberty, these rakehelly rides are the majority of his known fiction—assuming that Montgomery is not one of the many pseudonyms used by pulp writers. Per his Argosy biography, he might be one of many pulp writers to vanish into the Hollywood machine when Congress, paper shortages, and a new generation of editors sent them packing.

According to The Argosy Library:

"Much-revered and enjoyed by thousands of Argosy readers, these fast-paced stories have never before been reprinted."

That explains the paucity of information about the series, the characters, and their author. But does "A Sword for the Cardinal" live up to the ad copy?

It's a good start. The action is slick, with time and chance playing as big of a part as skill. It pays to be both good and lucky. And, like most pulps, "A Sword for the Cardinal" spends most of its time exploring the consequences of Guy's decision to turn his back on his political "friends" for the sake of his girl. Not all the resulting pyrotechnics are confined to action, either.

Comte Guy d'Entreville fills the same role as D'Artagnan, just for the Cardinal instead of for the King. He's young, foolish, brave, skilled, and proud—and of a higher station than Dumas' hero. But where The Three Musketeers villainizes Cardinal Richelieu, Montgomery portrays the Cardinal as a unifying force in France, clearing away the feudalistic barriers and privileges that leave France open to the machinations of Buckingham, Spain, and others. Although he has changed sides, Guy still fights for France--and his pride.

The highlight of the story is its ending. The Cardinal is saved, but deigns to dismiss Guy from his service. The rebuke to Guy's stiff pride is too much for the noble to bear. It is an insult to Guy to not be considered good enough to serve the Cardinal. His Catherine is freed, therefore he must serve the Cardinal as per their deal. In a roaring display of audacity, Guy forces the Cardinal to accept his service.

Just as Richelieu planned.

It's the mix of honor, integrity, and pride displayed in such a gesture that sets Guy apart from the procession of historical Argosy heroes. Competency is expected, as always, but there is a flair to all of Montgomery's characters not normally present. But if your heroes are going to pitch musketeers into fountains over questions of honor, style and swagger are required.

On the technical side, "A Sword for the Cardinal" is standard Argosy prose: clear, clean, and still contemporary almost 80 years later. As always, best to have a dictionary or encyclopedia handy. Not only does the text expect a certain familiarity with the historical setting, but a bit of French is also present. And, most pleasantly, this is not Three Musketeers fanfic or pastiche. As for the poetry present, whether Guy's verses are befitting a poet or a poetaster, I'll leave to those more qualified. Although that question is one argued throughout the series, with Guy cooling the heads of his most vocal critics on a regular basis—usually in the nearest fountain.

But I was promised the misadventures of a pair of rascals in the Cardinal's employ. And for that, we must read on.