Well friends, we are once again entering the shuddersome world of Karl Edward Wagner’s famous 39 List. Hopefully you all have enjoyed the ride so far. I for one have become deeply infatuated with the late Mr. Wagner’s predilection for the lesser explored avenues of pulp. Today, despite the high weirdness of our previous two entries, we stumble upon maybe the most grotesque and “out-there” novel of the entire list.

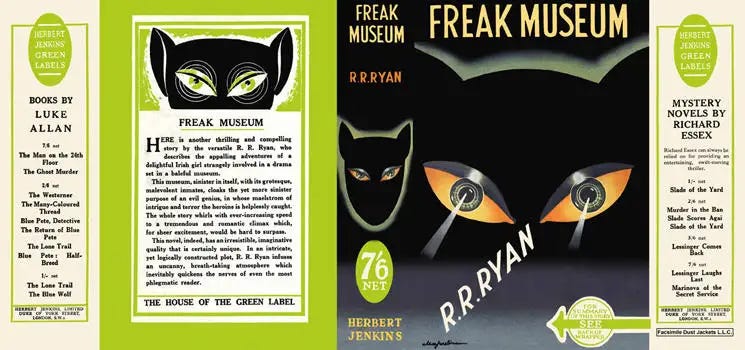

Published in 1938, R.R. Ryan’s Freak Museum is a gonzo novel—1/3 melodrama, 1/3 science fiction-horror, and 1/3 espionage story. For the first four chapters, one would be correct in thinking that Wagner had lost the plot. What’s so scary about an Irish immigrant moving to London in order to perform housework? I operated under the assumption that that was commonplace until about forty years ago. However, after chapter four, Freak Museum becomes a psychedelic and indeed disjointed novel that never fully lives up to its strange potential.

R.R. Ryan has the distinction of being the only author with three entries in the 39 List. And not just that, but Ryan’s three novels can be found in three separate categories: Best Supernatural Horror, Best Science Fiction Horror (where Freak Museum lives), and Best Non-Supernatural Horror. Wagner loved him some Ryan, and yet, despite this, little is known about Ryan outside of the three novels that Wagner chose to highlight. What can be said for sure is that Ryan was a British subject and a woman. “R.R. Ryan” was a pen name; her real one was most likely Denice Jeanette Bradley-Ryan. You ever hear the one about never trusting someone with two first names? Well, what about someone with FOUR of them? Ms. Bradley-Ryan may have been trustworthy in real life, but, as an author, she cranked out lurid and horrid tales during the mid to late 1930s. Freak Museum is one such novel, and like the other two praised by Wagner (Echo of Curse and The Subjugated Beast), Ryan’s specialty was the pulp sub-genre known as weird menace.

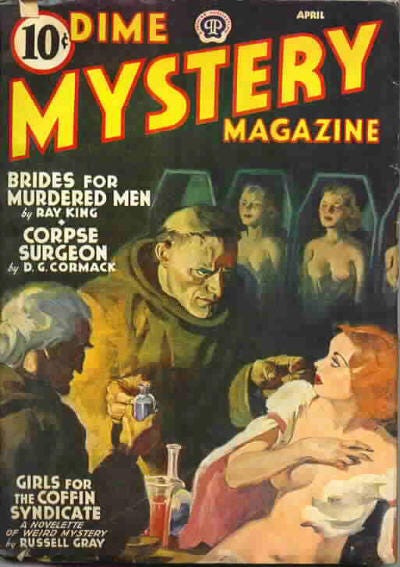

Brilliantly indexed and described by Robert Kenneth Jones’s in his book The Shudder Pulps, weird menace was an intentional mash-up of mystery and weird horror that was mostly produced by pulps like Dime Mystery Magazine and Dime Detective Magazine. In sum, weird menace tales presented highly sensational stories involving crimes committed by seemingly supernatural villains. In the end though, these villains are revealed to be nothing more than humans, usually either mad scientists, psychotics, or some kind of gangster-magicians. Basically, think 1930s Scooby-Doo with more sex and death.

Freak Museum is a thoroughly weird menace tale, but it is not as blunt as you may think. The story concerns two unfortunate souls. The first is the Irishwoman Bridget O’Malley. Following the death of her lover, a pregnant O’Malley is left stranded and alone in Dublin until she gets an invite to London. There, in the imperial metropole, O’Malley eventually gives birth to a baby. But the baby dies. Or at least she is told of its death by two shady individuals. The first is a doctor named Stettin. Stettin is a creepy sawbones whose terrible physiognomy inspires O’Malley to call him “the Tapeworm.” Stettin is a Teutonic immigrant (later revealed to be an Austrian of “Semitic” origin) who runs a private hospital. Next door is an establishment run by a certain Mr. Axe, who also tells O’Malley about the unfortunate loss of her child. Mr. Axe is much smoother than Stettin—he is suave, a businessman, and someone capable of moving in and out of high society. Mr. Axe’s establishment is the Freak Museum, which puts human perversions on display for the public’s enjoyment. Such freaks include the Centaur, the Elephant Woman, the Tiger, the Swordfish, and, most loathsome of all, the Octopus. These freaks are captives in the museum, and before long, O’Malley becomes a prisoner as well.

Halfway through the novel, a certain Robert Passport stumbles upon the museum’s secrets. Passport is a former global traveler—a part-time poet, artist, mercenary, waiter, lumberjack, and gadfly. Passport is also made a prisoner, and after falling in love with O’Malley (dubbed “Shamrock”), he conspires to free everyone, even including the freaks.

So why all the confinement? What drives Stettin, Axe, and their four freak bodyguards to keep Passport, O’Malley, and the others as prisoners? Freak Museum hints that the motive is global in scale. Namely, Axe and Stettin are spies for a foreign government and they want to use O’Malley as a kind of honeypot to entice a major figure within the British government. One of the running gags in the book is that Axe and Stettin refuse to disclose their paymasters, thus forcing O’Malley and Passport to vocally denounce Soviet communism, Italian fascism, and National Socialism all at the same time. We never learn the truth; we only hear that Stettin and Axe are champions of an undefined dictatorship. (That being said, in one scene, Axe is protected by bodyguards in blackshirts.) Passport, a British subject whose long stay in New York has turned him into a quasi-American, even including his speech patterns, makes the case for the British Empire during one of Axe’s interrogations.

One’s always hearing that the British Empire’s got the dry rot, that it’s going to crumble to bits—but it doesn’t. It muddles on; not because we’re cleverer than other nations, we’re not; nor do we think we are—we merely appear to do so. We’re neither as clever nor as thorough, nor as consistent. But we’re moderate. We’re the happy mediumers. We don’t dictate—we only insist. Extremes in any shape or form, of any nature are not good for life; they distort it.

Curiously, neither Axe nor Stettin try to refute this, and ultimately, their plot goes belly-up. It all ends in a secret death room where corrosive acid and mechanical doors hold the keys to fate. What that fate is is never directly stated. Indeed, there are more suggestions than answers in Freak Museum. We don’t know the particulars of the dictatorship plot, and likewise we do not know for sure whether or not the freaks are natural or are the results of Stettin’s scalpel. The implication seems to be that the monstrosities were purposely created. Then, with the sweet Elephant Lady and the wise Centaur, it is more or less said that they have been freaks their whole lives. Maybe some freaks were made, and others were born.

This is the central issue with Freak Museum—it is a book that is trying to do a lot at once, and when it comes time for the payoff, the reader is left holding more of the bag than they’d like. The concept is stellar, but the final product is a tad bit shabby. Add to this Ryan’s habit of writing ironically (there’s loads of winks and nods to the audience), and Freak Museum can at times come across as a novel trying too hard to be weird. Still, it is an enjoyable read, and the sheer insanity of the story helps it to limp along.

2.9 out of 5 stars.