Absolute dominion of a powerful people by a minority always produces national aggression.

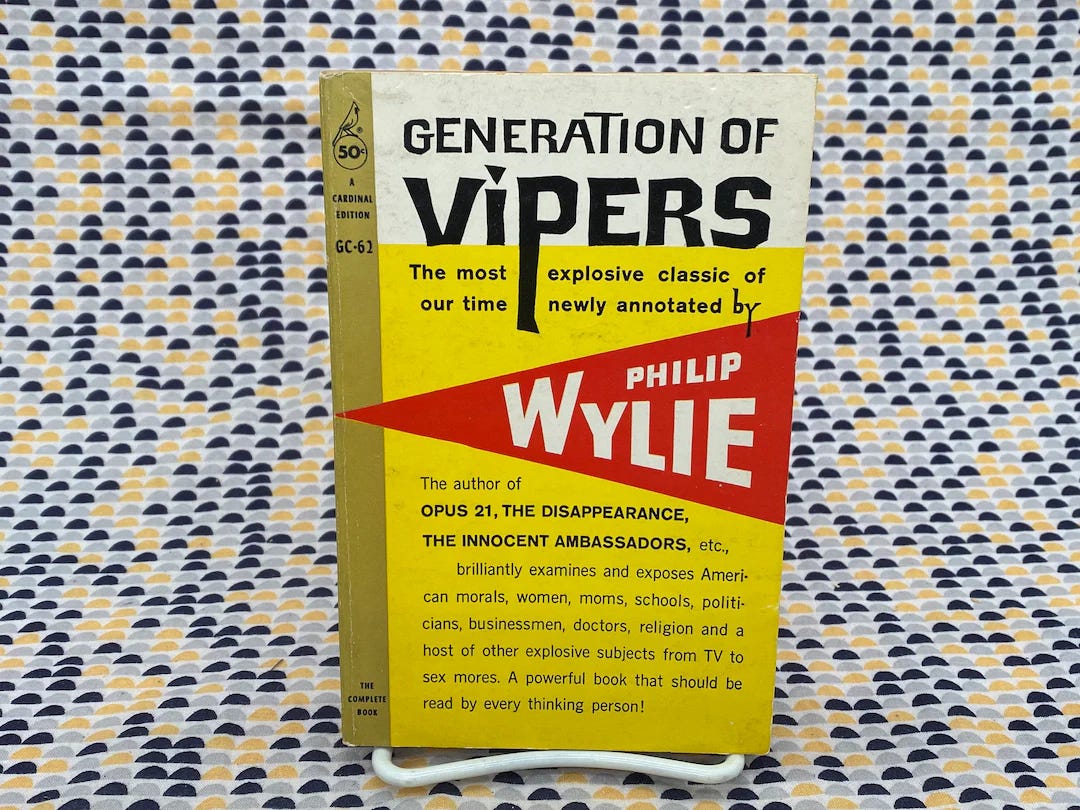

—Generation of Vipers (1943)

Philip Wylie never minced words. Whether in his fiction or essays, Wylie always provided the blunt truth, or at least the blunt truth as he perceived it. A writer, critic, and something of a prophet, Philip Wylie lived a life of an unchained mind, and for that he continues to be punished by the select few who know his name.

Philip Gordon Wylie was born on May 12, 1902. The son of a Presbyterian minister father and a novelist mother, Wylie spent his formative years in Beverly, Massachusetts and Montclair, New Jersey. When young Philip was five, his mother, Edna Edwards Wylie, died as a result of medical malpractice. This event scarred Wylie like no other. His beloved mother became the ideal to which no other woman could aspire. This personal cult of Edna Wylie would go on to influence Wylie’s most notorious work—1943’s Generation of Vipers. As for his father, Edmund Wylie used a stern hand on his son. The high moralist Edmund also had a mean streak. He had his son circumcised without anesthesia at eighteen months. Even worse was Edmund’s decision to remarry. Philip considered this the ultimate betrayal.

The bookish and introverted Wylie proved a natural at naturalism. He excelled in the Boy Scouts. His love of the outdoors proved so strong that he delayed his enrollment at Princeton in order to conduct a wildlife expedition in Canada. Wylie attended Princeton for three years without graduating. Subpar grades and a spat with a professor caused his early exit. Although an Ivy League dropout, Wylie still managed to acquire positions with the California Institute of Technology and the Lerner Marine Laboratory later in life on the strength of his autodidacticism.

From 1925 until 1927, Wylie wrote for the New Yorker. After being released from the magazine, Wylie went to work as a freelance writer. This would be his bread and butter for decades. Wylie would later surmise that he wrote some fifty million words in his lifetime, and given the breadth of his written work, with everything from science fiction novels to scientific papers to his credit, the number does not seem outlandish.

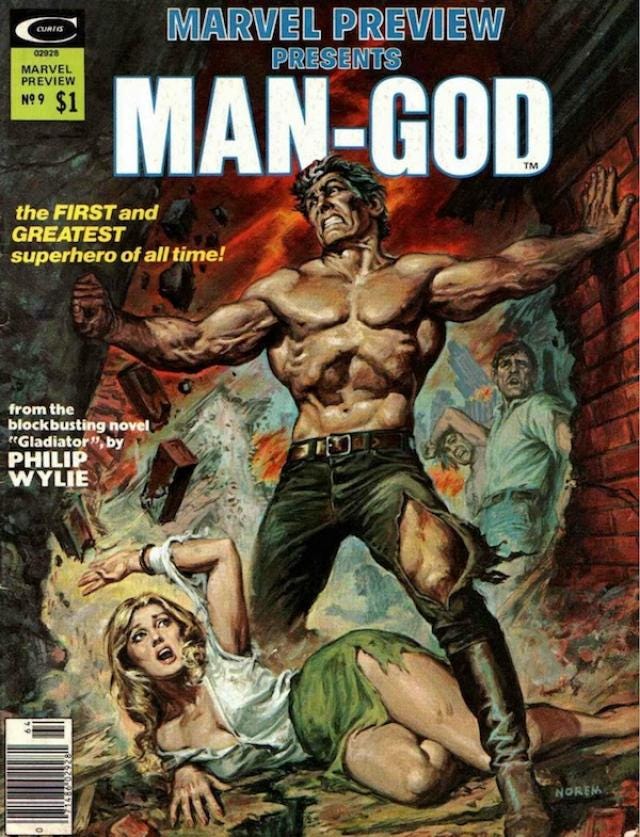

Wylie excelled as a pulp writer specializing in speculative fiction, particularly science fiction novels. 1930’s Gladiator set the blueprint for Wylie’s more influential work. Gladiator tells the tale of Hugo Danner, a genetically superior specimen born with extraordinary speed and strength. Thanks to these abilities, Danner becomes a sports hero, a war hero, and sideshow act. Fame, however, does not dull Danner’s problems. Gladiator is primarily a character study of a unique individual living in a conformist society. The book would go on to directly inspire both Doc Savage and Superman.

Gladiator was followed by 1932’s The Savage Gentleman, a black comedy of sorts about a tall, tanned, and handsome man groomed to loathe women. Of all of Wylie’s literary efforts during this period, none proved more popular than 1933’s When Worlds Collide. Co-written with Edwin Balmer, When Worlds Collide is an apocalyptic science fiction novel about the discovery of two planets—Bronson Alpha and Bronson Beta. Swedish scientist Sven Bronson realizes that the two planets are destined to cause gravitational damage to Earth which will result in humanity’s evisceration. As such, Bronson and others work to create a rocket ship designed to ferry humans to safety to the inhabitable Bronson Beta. The problem that this team keeps encountering is the mindless mob that sees no issue with destroying Bronson’s experiments. When Worlds Collide was adapted as a film in 1951.

Speaking of Hollywood, Wylie began producing screenplays after his 1931 novel The Murderer Invisible became a motion picture. He provided uncredited work for Erle C. Keaton’s Island of Lost Souls, a highly controversial adaptation of H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau that was banned outright in the United Kingdom, Germany, New Zealand, and other countries. Wylie’s next screenplay proved no less problematic, as 1933’s Murders in the Zoo would be banned in Germany and Sweden and only shown in certain American states and Canadian provinces after heavy editing. Wylie’s name was somehow not tarnished by his association with these “dangerous” flickers. He would continue to pen screenplays for Hollywood until 1966. Some of this work included adaptations of his own novels. However, Wylie primarily wrote potboiler mysteries for the movies, including one for the Charlie Chan series.

Wylie’s successful professional life did not mirror his personal one. A turbulent drinker, Wylie’s first marriage ended in the early 1930s. Before the divorce, Wylie’s wife had him briefly committed to a psychiatric hospital in New York. There, Wylie developed an interest in Jungian psychoanalysis after conversing with one of his doctors. Depressed and alone, Wylie devoted himself to getting rich by writing popular fare for the masses. In 1935, he made $40,000, a kingly sum during one of the worst years of the Depression.

During World War II, Wylie went to work for the U.S. government. Specifically, he penned propaganda pieces for the Office of Facts and Figures. This job came to a close when Wylie failed to convince his superiors that telling the American public about the Bataan Death March and other Japanese atrocities would stir up patriotic feeling. Angered by his rough treatment, Wylie returned to his home in Miami Beach. There, between May and July 1942, he hacked out what would become Generation of Vipers—an acerbic takedown of the feminization of American society.

Wylie’s best-known and most infamous work, Generation of Vipers sold out not long after its January 1943 release. Seven years later, the American Library Association listed it as one of their 50 most influential and important books of the last 50 years. Yet, despite this praise, Wylie’s seminal work is held up today as an example of unbridled misogyny. In the book, Wylie excoriates American motherhood for creating a false “Cinderella” tale for young girls wherein in they are told to expect material wealth “merely because they are female.”

“The idea women have that life is marshmallows which will come as a gift — an idea promulgated by every medium and many an advertisement — has defeated half the husbands in America. It has made at least half our homes into centers of disillusionment. […] It long ago became associated with the notion that the bearing of children was such an unnatural and hideous ordeal that the mere act entitled women to respite from all other physical and social responsibility.”

Elsewhere, Wylie bemoans the decline of filial duty and its replacement by an unthinking worship of the “mom” figure. Wylie dubbed this cult “Momism.” At the heart of Momism are haggard, ugly women who gossip, smoke over thirty cigarettes a day, and distract themselves with soap operas and heavy drinking and eating bouts. These “Moms,” Wylie notes, are also easy to rile up to political action.

“Mom is organization-minded. Organizations, she has happily discovered, are intimidating to all men, not just to mere men. They frighten politicians to sniveling servility and they terrify pastors; they bother bank presidents and they pulverize school boards. Mom has many such organizations, the real purpose of which is to compel an abject compliance of her environs to her personal desires.”

Wylie’s Momism bears a striking resemblance to the “longhouse” phenomenon most recently articulated by Twitter personality Lomez in a highly controversial article for First Things. Generation of Vipers attacks modern women for their preference for safety and complete control, along with their repugnance for all things masculine. These themes would reappear in Wylie’s 1949 novel Opus 21, which contains several passages deriding the prevalence of single mother households, especially those wherein single mothers raise (or rather attempt to raise) sons. The point of it all, according to Wylie, was Momism’s success at castrating young men and turning them into good, docile worker bees for corporations.

The success of Generation of Vipers did not dampen Wylie’s enthusiasm for the written word. He continued to churn out novels well into the 1970s. Sometimes these novels got him in trouble. One, 1945’s The Paradise Crater, a novelette about a German atomic attack on the United States, earned Wylie a stint under house arrest courtesy of Army Intelligence. The U.S. government did not like the idea that a civilian pulp writer knew so much about atomic weapons, especially since Wylie’s work appeared in print well before Hiroshima. Oddly enough, Wylie’s decades-long plea for an atomic energy agency controlled by the civilian government came to life after the war with the creation of the Atomic Energy Commission. Wylie would continue to warn of atomic and ecological disasters in his fiction during the Cold War era. Tragically, a more earthbound disaster struck the Wylie family on August 28, 1963, when his niece Janice Wylie, a researcher for Newsweek and the daughter of the creator of the television show The Flying Nun, was murdered along with her roommate Emily Hoffert in their New York apartment. This crime, known as the Career Girls Murder, became a tabloid sensation.

Wylie passed away at his Miami Beach home at the age of sixty-nine on October 25, 1971. He was survived by his second wife Frederica Ballard and daughter Karen Pryor. Wylie’s influence is as outsized as it is overlooked. Few today recognize his name, nor his contributions to pulp fiction, super-hero fiction, and certain strands of right-wing thought. Wylie also penned some world-class screenplays for films that became classics long after their initial infamy. That is the story of Wylie’s life and work: he was a brazen visionary who had an almost preternatural gift of foresight. The man considered a resentful and cruel-hearted woman-hater suffered for his art. And yet this art lives on as a small, mostly unseen flame flickering against the winds of time and popular opinion.

This is important work sir, I'm looking forward to a collection of these critical essays of yours in a volume. Writers such as Wylie ought to be remembered and their work studied.

Thanks for this post. I didn't know about Wylie before this, but I will check out his work now.