Graphic Pulp: In Praise of Ed Brubaker

The Arbo Files

When the pulp era ended, the comic book era arrived. Beginning in the late 1940s, the so-called '“funny books” replaced the pulps as the go-to reading material for America’s working class. However, unlike the pulps, the comics were primarily meant for children, hence the garish colors, outlandish plotlines, and reliance on images rather than prose. Kids loved the superhero stuff, of course, but they also dug the horror and crime comics that dominated drug store shelves all across the U.S. These titles excelled at excessive violence and gore, and often times they barely fictionalized real crimes. EC Comics became the flagship company for such sicko entertainment, with their Tales from the Crypt series being the most well-known example. Unsurprisingly, America’s parents hated these comics, and thanks in part to fears about rising juvenile delinquency levels, pressure mounted for the government to take action.

In 1954, a Senate sub-committee was convened on the topic of juvenile delinquency. The “comic book menace” was front and center at the hearings. Leading the crusade against the “ten-cent plague” was psychiatrist Dr. Frederic Wertham. After spending years working primarily with juvenile offenders in New York City, Wertham penned the bombshell book, Seduction of the Innocent. In the tome, Wertham excoriates comics for inducing in impressionable children an appetite for sadism, sexual debauchery, and general degeneracy. Some of the cases the book details are sick, and it also true that most of Wertham’s highly disturbed patients were avid readers of comics. However, Wertham took these two facts and ran wild with them, going so far as to tell American senators that, “Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry.”

The credentialed exaggeration worked. EC Comics went under in the mid-50s, and the comic book industry created a governing board called the Comics Code Authority that effectively neutered the industry until the 1980s. Safe and for kids—that’s the culture that Comics Code Authority created.

By the time Ed Brubaker began publishing, the comic book industry had long shed its reputation for soft stuff. The son of a Navy intelligence officer who grew up living the vagabond life that all military brats know, Brubaker started writing and drawing underground comics in the late 1980s. Given his long-time residence in the Pacific Northwest, Brubaker’s work has always had a kind of low-fi, hipster-in-the-rain quality. The fact that Brubaker cut his teeth in the indies further solidifies this image of him as a cooler-than-you comics creator.

But here’s the punch and kicker about Brubaker: he is a devotee of pulp. Brubaker’s best work always features crime, sex, and sometimes horror. The man is also prolific like the pulpsters of old. He has written scripts for Detective Comics, Batman, Catwoman, Captain America, and many more. He got in the screenwriting game in 2019 with the Amazon series, Too Old to Die Young, which Brubaker co-created with Drive director Nicolas Winding Refn.

But, and this cannot be stressed enough, Brubaker’s true talent lies in writing noir comics. Brubaker’s writing is easily identifiable— it combines hardboiled terseness with a consistent focus on interiority, i.e., the troubled thoughts of his low-life protagonists. Brubaker’s excellent prose pairs best with the cool and jazzy expressionist art of Sean Phillips. Together, Brubaker and Phillips have been responsible for the best graphic literature of the last fifteen years or so. If you have yet to read this lit, then use this here post as a primer.

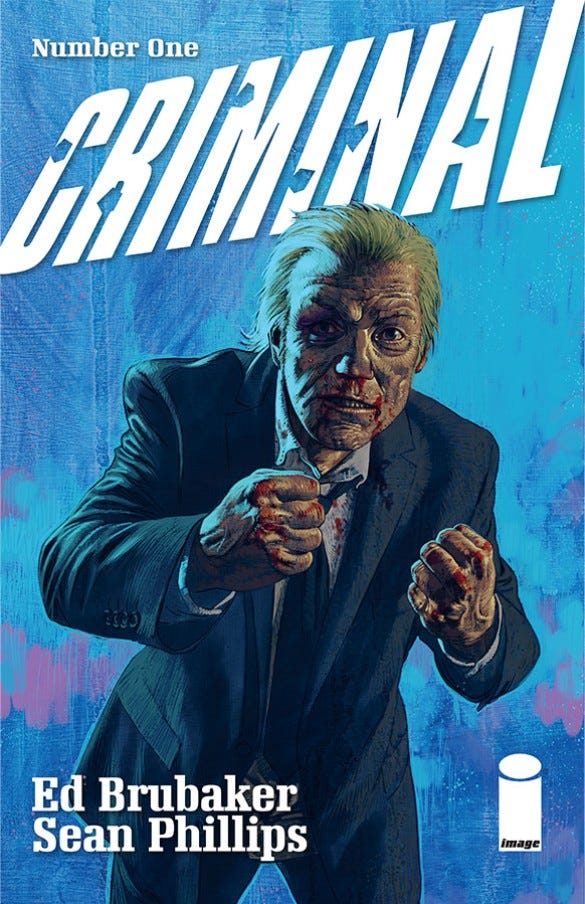

The oldest and longest-running title in the Brubaker-Phillips oeuvre, Criminal is about an interconnected world of thugs in an unnamed city somewhere out west. First published in 2007 and currently in hiatus, Criminal features stand-alone graphic novels about crime and the criminals who commit them. The first in the series, Coward, focuses on the pickpocket Leo. Leo plays it as safe as a crook can. He does not allow guns on his jobs, and the moment something goes wrong, he bails. He is a “coward” in underworld parlance because he refuses to take risks. Well, risks find Leo anyway in Coward.

A majority of the Criminal titles, from Lawless (2007) to The Sinners (2010), feature both the AWOL soldier and hitman Tracy Lawless and the Hyde crime family. While Lawless is the bloodied, but still moral paladin who pursues his own vendettas, Sebastian Hyde and his crew are the epitome of ruthless mafia capitalism.

The best in the series is 2009’s Bad Night. Jacob Kurtz is a sleepless comic strip creator who gets involved with the wrong chick. When a pair of stumblebum crooks try to utilize Kurtz’s forgery skills, everything goes south. A vengeful detective, a femme fatale, and a dissociative state that is represented by one of Kurtz’s comic strip characters coming to life—Bad Night has got it all in spades.

Originally published as a limited series between December 2008 and August 2009, Incognito is set in a United States where pulp fiction superheroes and villains are real. One of the latter, Zack Overkill, was placed into the Witness Protection Program after he provided the feds with information about the supervillain known as the Black Death. In order to stay in Witness Protection, Overkill has to take experimental drugs that dull his powers. Overkill soon gets bored with his mailroom job and the lack of excitement in a working stiff’s life. He finds release in illicit narcotics. Then, thanks to a less-than-savory co-worker, Overkill begins doing bad deeds again. At the same time, the Black Death’s henchmen try to eliminate Overkill before he can provide further testimony. Incognito describes Overkill’s fight against the Black Death, as well as his reluctant examination of his own origins.

If you can, track down the single issues of Incognito. Each one of these monthly gems contains an article highlighting obscure characters and themes from the golden days of the pulp magazines.

While Incognito is influenced by the golden age of pulps, The Fade Out (2014-2016) is about the golden age of Hollywood. Set during the first days of the Cold War, The Fade Out is a murder mystery with an unusual detective. The man who takes the lead on solving the murder of up-and-coming starlet Valeria Sommers is the alcoholic and PTSD-riddled screenwriter Charlie Parish. Besides being a hack who does not write his own scripts (that work is done by the blacklisted Gil Mason), Parish also has a guilty conscience. Parish blacked out on the night of Valeria’s death. He also found her dead in his apartment. Therefore, Charlie’s hunt for the truth is really about clearing his name.

The Fade Out is a mostly successful reproduction of the paranoid world of postwar Hollywood. It accurately depicts the realities of the studio system, as well as the power of the media and the FBI during that time. Also, The Fade Out pulls no punches in showing just how long pedophilia and satanic sexual abuse has been a thing in Tinseltown.

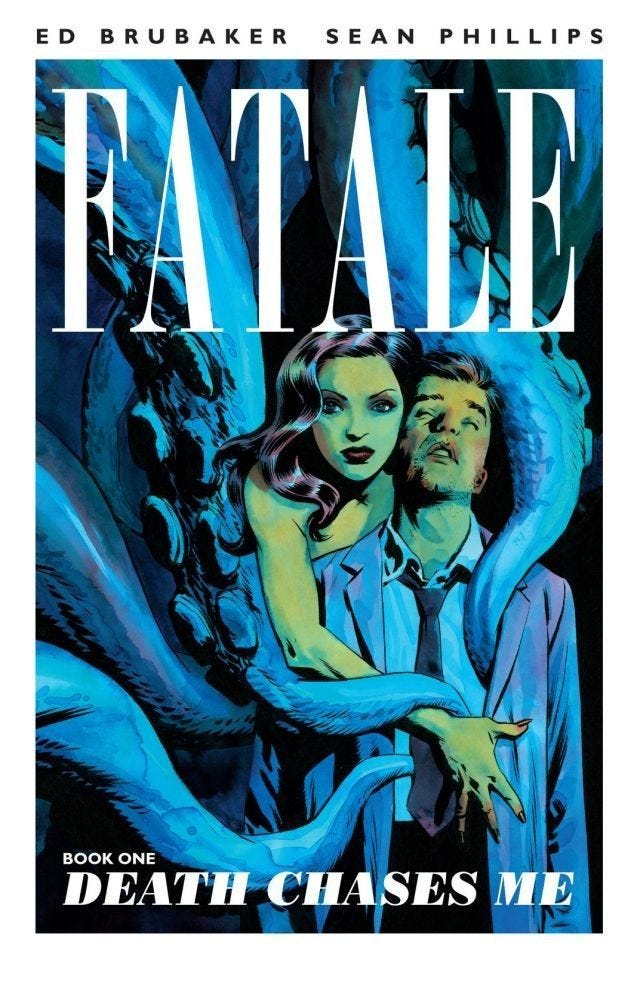

You cannot be a pulp writer without doing something Lovecraftian at least once. Welp, Brubaker and Phillips did just that with Fatale (2012-2014). Unlike most of Brubaker’s work, the protagonist of Fatale is female. Josephine (Jo, for short) is a beautiful but dangerous femme fatale who has a bad habit of driving men insane. Yes, she is good looking. Yes, she is ageless. But Jo’s true power is much more cosmic — she is an immortal eldritch monstrosity. Something of a siren, Jo lures unsuspecting men to their deaths. It is her curse. Like The Fade Out, Fatale covers American history and our country’s stygian network of occult societies. Jo is an unwitting horror, but a horror all the same.

If you can get the monthly issues of this series, please do it. Like Incognito, Fatale’s single issues all feature great essays by the likes of Jess Nevins and Charles Kelly about Lovecraft, cults, and underappreciated crime fiction writers like Dan J. Marlowe.

The most recent series by Brubaker and Phillips, Reckless (2020 -) tells the tale of unlicensed private eye Ethan Reckless and his assistant Anna. Set in 1980s Los Angeles, Reckless is incredible crime fiction told with two fists. Reckless is a burned-out former FBI asset who went rogue after being assigned to infiltrate left-wing terrorist groups. As for Anna, she is a punk rock runaway who joins Ethan at El Ricardo, an abandoned cinema that becomes Reckless’s residence.

So far, the tales have followed a formula familiar to all detective fiction readers: Ethan is contacted by someone looking for a missing person or revenge. Ethan takes the case. Anna does the research while Ethan does the fighting. Most of the stories touch on something from Ethan’s past. There are some exceptions. The Ghost in You (2022) has Anna front and center. Here, the plucky projectionist investigates a missing dog and a supposedly haunted house. The best of the bunch is 2021’s Friend of the Devil. After a Vietnamese American librarian asks Ethan to find her lost half-sister, Reckless uncovers a world of satanic cults and low-budget cinema. It’s all sleaze, and that’s a good thing.

If you have not read comics in a while, then get back into the funny papers by digging through the Brubaker-Phillips oeuvre. These books are pure pulp, and nice to look at too. Fans of crime fiction, hardboiled noir, and weird horror will find what they hunger for in this world. So, start eating, ya freaks!

this was excellent... it also gave me the missing piece of the puzzle I needed for a new short story I am writing (you know how those thoughts circulate in the head when you listen to other plots...) :)

Well done. I'm a big fan of Philips and Brubaker. Enjoyed The Fade Out and Criminal. Recently picked up the first Reckless book. Now I need to find Incognito - sounds right up my alley.

These articles never disappoint. Excellent work!