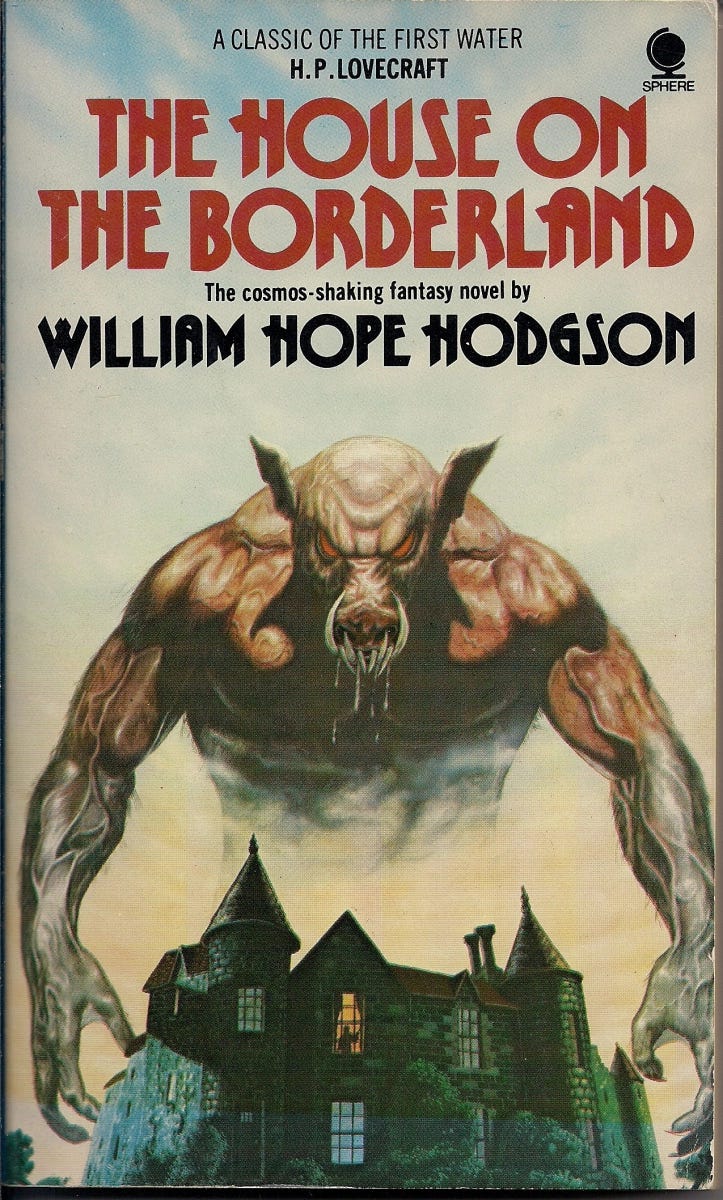

In case you are unaware, we at the Bizarchives are currently selling a beautiful volume. The book is entitled, The House on the Borderland. In its current iteration, the novel is a free eBook for the loyal and faithful among you, the PVLP KVLTISTS. But, back in 1908, The House on the Borderland hit the shelves courtesy of publishers, Chapman and Hall. A strange tome, The House on the Borderland startled Edwardian era readers with its unusual approach to horror. Rather than conform to the well-known and well-worn trappings of Gothic horror, the novel struck out for weirder waters, with cosmic elements enveloping the known world via an odd little house in Ireland. One fan of the novel wrote,

“The House on the Borderland (1908) … tells of a lonely and evilly regarded house in Ireland which forms a focus for hideous otherworld forces and sustains a siege by blasphemous hybrid anomalies from a hidden abyss below. The wanderings of the Narrator's spirit through limitless light-years of cosmic space and Kalpas of eternity, and its witnessing of the solar system's final destruction, constitute something almost unique in standard literature. And everywhere there is manifest the author's power to suggest vague, ambushed horrors in natural scenery. But for a few touches of commonplace sentimentality this book would be a classic of the first water.”

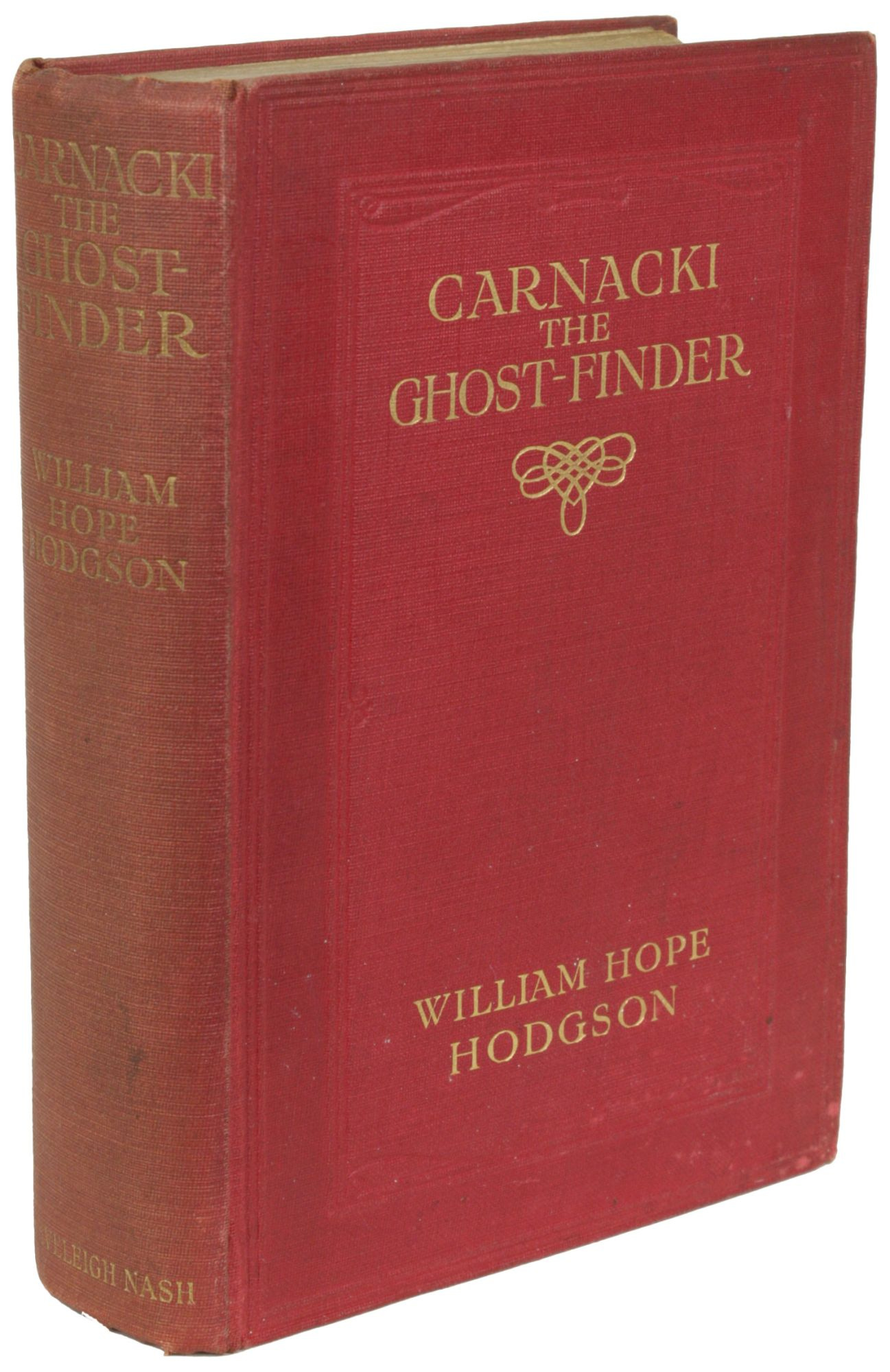

Who wrote this glowing review? None other than H.P. Lovecraft, who sung the novel’s praises in his lengthy essay, Supernatural Horror in Literature. Lovecraft also spoke of the novel in his letters to friends, including one missive to fellow pulp author August Derleth. In a letter dated August 6, 1934, Lovecraft wrote, “‘The House On The Borderland’ has a breath-taking cosmic reach. No comparison is possible between these fine works & Hodgson's later feeble attempt — ‘Carnacki the Ghost Finder’ — which I read in Florida.” Clearly, the man most closely associated with weird fiction thought very highly on this obscure novel. Lovecraft counted its author, William Hope Hodgson, among his chief influences.

Who was William Hope Hodgson? What kind of life did he lead? How did he come to write such a harrowing and highly influential novel?

William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918) came into the world as the son of a priest. Born near Braintree, Essex to an Anglican clergyman, Hope (as he was known to friends and family), was the second of twelve children. He was one of the lucky ones, as three of the family’s children died in infancy. Death and turbulence became a theme in Hodgson’s young life. His father, Reverend Samuel Hodgson, served at least eleven different parishes, including one in County Galway in Ireland. Thus, as a child and young adult, Hodgson lived all over the British Isles and experienced the many rich and varied cultures of the Anglo-Celtic homeland.

Restlessness proved to be a curse and a blessing for Hodgson. At age thirteen, he escaped from boarding school and tried to make it as a sailor. Captured and returned to his family, the elder Hodgson made the surprising decision to bless his boy’s thirst for the sea. In 1891, Hodgson received a four-year apprenticeship as a cabin boy. Hodgson loved the sea, and the sea loved him back. The pair would know each other well for years. The sea toughened Hodgson up in more ways than one, too. The future author began his sailing career as a shy, short, and thin waif. Shipboard bullies tormented him until Hodgson grew a spine. When shore leave presented itself, Hodgson purchased weights and a heavy bag in order to begin his physical education. Before long, the once skinny young lad became a muscular powerhouse who published tracts on the importance of weightlifting. All that training proved useful on March 28, 1898, when Hodgson saved a fellow sailor’s life after the latter fell overboard near Port Chalmers, New Zealand.

“On the 28th March, 1898, a man accidentally fell overboard from his ship in the harbour at Port Chalmers, New Zealand, the distance from shore 600 yards 25 to 30 feet deep, and the water infested with sharks. W.H. Hodgson, ship’s apprentice, jumped after him, and kept him afloat for 25 minutes, when they were picked up by a boat half a mile from the ship…”

A year later, Hodgson quit the sea and settled himself in the English city of Blackburn. There he opened his own gym. Hodgson’s enthusiasm for bodybuilding was not shared by the general public at the time, and his gym went belly-up. Hodgson may have taken some of this aggression out on escape artist Harry Houdini (a future writing partner of Lovecraft’s), who accused Hodgson of deliberately hurting him during a demonstration in Blackburn.

At this time, Hodgson began to explore his other interests, such as photography, natural sciences, and writing. Hodgson’s first articles concerned exercising and sailing. In one fiery piece, Hodgson attacked the apprenticeship policies of the Merchant Navy. In others, he went into great detail about his life at-sea. It was not until 1903 or 1904 that Hodgson turned his pen to fiction. His first published story, “The Goddess of Death,” appeared in 1904 (some sources say 1906).

Hodgson published his first novel, The Boats of the “Glen Carrig” in 1907. The adventure and survival story is rarely counted among of Hodgson’s best, but it is nevertheless incredible that such a novice writer could churn out and publish a full-length novel less than five years after first putting pen to paper. Furthermore, The Boats of the “Glen Carrig” deftly displays Hodgson’s knack for creating disturbing scenes, as the shipwrecked survivors find themselves adrift on the Sargasso Sea—a ghost-choked swamp full of derelict reefs, gigantic monsters, and unnamable things beyond human comprehension. Hodgson’s Sargasso Sea became one of weird fiction’s first imaginative realms. Like the so-called Lovecraft Country of Arkham, the Miskatonic River, and Dunwich, Hodgson’s Sargasso Sea provided a backdrop for future unsettling tales my multiple authors.

A year later, The House on the Borderland was published. A true masterpiece of the weird fiction style, the novel features a damned house in Ireland that is a sort of portal between worlds. An infernal pit on the dwelling is the cause of much dislocation. Said dislocation includes not just the complete collapse of time and space, but also the appearance of extraterrestrial creatures that must have scared the bejeezus out of readers in 1908. YOU SHOULD READ THE BIZARCHIVES VERSION OF THE BOOK RIGHT NOW, READER!

Hodgson’s output continued to increase after 1908. In 1909, the novel The Ghost Pirates was published. This was followed by what many consider to be Hodgson’s greatest achievement, 1912’s The Night Land. A massive, 500-page plus tome, The Night Land blends horror, high fantasy, and science fiction in a tale about the last traces of humanity entrapped in a metal pyramid known as the Last Redoubt. Besieged by dark powers, the survivors in the Last Redoubt seek connection with their fellow humans at the Lesser Redoubt via astral projection. Although death is almost certain, a brave selection of the people from the Last Redoubt conduct an expedition to the Lesser Redoubt. What follows is among some of the most mind-bending fiction ever penned, especially given that it appeared long before the Internet and the proliferation of hallucinogens. Also, as an aside, Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series owes more than a few “thank yous” to The Night Land.

Hodgson wrote cutting-edge weird fiction, but said fiction did not make much of a dent during his lifetime. Rather, Hodgson had devoted fans mostly thanks to his creation of Carnacki, the Ghost-Finder. First appearing in 1910, Carnacki is something of a supernatural Sherlock Holmes, with clients regularly meeting him at his London address in order to discuss ghosts, demons, and sundry elementals. Hodgson’s Carnacki stories captivated magazine readers from 1910 until 1913. The best of the bunch, such as “The Whistling Room,” continue to be anthologized. The Carnacki stories are excellent fun, but, to paraphrase Lovecraft, one of the biggest Carnacki detractors, they are formulaic in the extreme. One gets the impression that Hodgson wrote Carnacki for money and not much else. Still, Hodgson’s pen was so mighty that even his cynical cash-grabs are superior to most modern content.

Hodgson moved to London around 1911 to pursue writing full-time. Marriage and another move, this time to Paris, characterized Hodgson’s life until 1914. In that year, the Great War erupted all across Europe and her colonial dependencies. Hodgson, a man of action as well as a man of letters, signed up for the British Army’s Officer Training Corps program at the University of London. (The Royal Navy tried to sway the sailor Hodgson back to the sea, but he stuck to land and the army.)

Hodgson earned his commission as a Lieutenant with the 171st Battery of the Royal Field Artillery. In this capacity, Hodgson was required to undergo cavalry training. Hodgson fell off his horse soon thereafter, and his injuries included a serious concussion as well as a broken jaw. Due to his injuries, Hodgson was discharged and sent home. This did not last. Hodgson re-enlisted in October 1917. He joined the 11th Brigade, 84th Battery. His first assignment was the charnel house at Ypres.

From 1914 until the war’s end in 1918, Ypres, Belgium saw intense fighting between Germany and the Entente powers of Great Britain (including her Canadian soldiers, who distinguished themselves as crack troops during the five battles of Ypres), France, and Belgium. The Fourth Battle of Ypres (also known as the Battle of the Lys, April 7-29, 1918) would claim well over one hundred thousand men on both sides. Among the casualties was Hodgson. Sometime between April 17 and 19, Hodgson, who had a reputation as a daredevil who always volunteered for the most dangerous missions, was fatally struck by an artillery shell. In a letter to Hodgson’s window, his commanding officer remembered the writer-warrior as an officer of outstanding character:

“I cannot express my deep sympathy for you in your great bereavement. I feel it most terribly myself, and so do all the other officers and men of the battery. He was the life and soul of the mess—always so willing and cherry. Of his courage I can give no praise that is high enough. He was always volunteering for any dangerous duty, and it was owing to his entire lack of fear that he probably met his death on April 17. He had performed wonders of gallantry only a few days before, and it is a miracle that he survived that day. I myself am deeply grieved, having lost a real, true friend and a splendid officer.”

A hell worse than any one of Hodgson’s creations cut his life short at just forty. He left behind not just a wife that loved him, but also a surprisingly large body of work, including fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Hodgson inspired so many writers, and did so much to influence the direction of weird literature in a single decade of writing. Most scribblers cannot even touch a tenth of these accomplishments in a lifetime.

A visionary and true hero, William Hope Hodgson should inspire the PVLP KVLTISTS of today to strive to achieve greatness—greatness in their body, their work, and legacy. The gentle clergyman’s son grew up to become a British lion of incredible power. That personal story is made all the more captivating by Hodgson’s unrivaled creativity. And now, thanks to the Bizarchives, that creativity is being exposed to a new audience eager for glory of the kind achieved by William Hop Hodgson.

thoroughly enjoyed this, had to laugh aloud with the Houdini anecdote! Hodgson's 'strange' fiction was an early read of mine.