“Only optimists commit suicide, optimists who no longer succeed at being optimists. The others, having no reason to live, why would they have any to die?”

—Emil Cioran

Weird fiction, most notably the cosmic variety most closely associated with H.P. Lovecraft, is full of foreboding, of dread, and of despair. In the argot of the Internet, it is “blackpilled.” Much the same can be applied to Lovecraft himself, who lived a lonely life often without work or much purpose. Granted, Lovecraft’s voluminous letters to friends and acquaintances show that he had a social life, and the Old Gentleman from Providence was hardly a recluse. Heck, unlike an alarming number of men aged 25-45, Lovecraft had a wife, albeit for only a brief time. However, given Lovecraft’s philosophy of weird fiction, plus his liminal lifestyle as a man of out-of-time within the twentieth century, the popular image has already been set in stone: Lovecraft was a loner misanthrope who lived and died in obscurity.

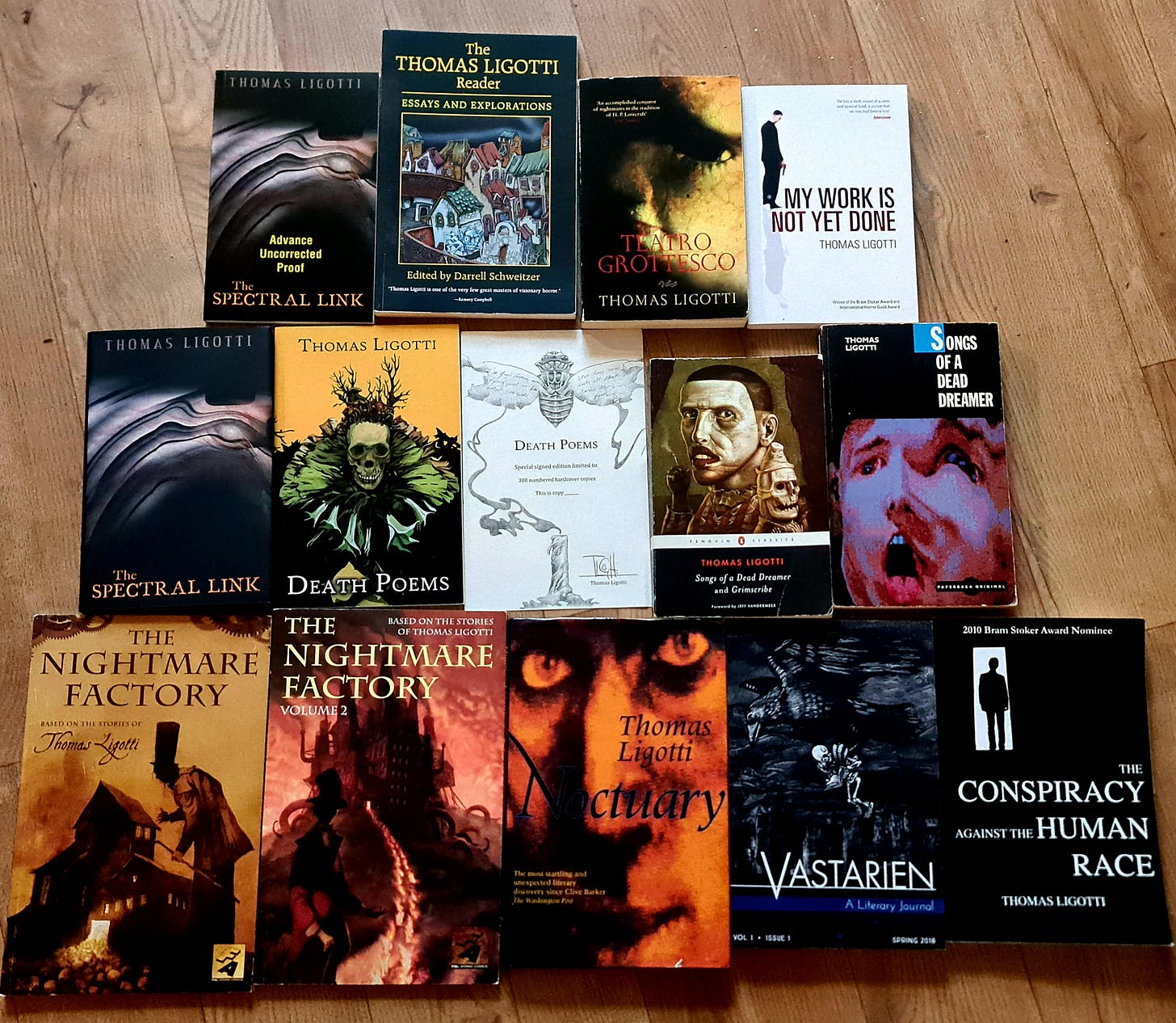

While this image of Lovecraft is an exaggeration often at odds with reality, it is much closer to home when it comes to one of Lovecraft’s disciples, the contemporary weird fiction author Thomas Ligotti (1953— ). As well-respected as Mr. Ligotti is within the confines of weird fiction, there is scant information about him online or in-print. His biography only provides the barest shadows. He was born and educated in the Detroit, Michigan area, and for most of his life he has worked in publishing. Ligotti first began publishing his odd short stories in small press magazines in the early 1980s. Underground renown and critical acclaim came in the same decade thanks to his collection Songs of a Dead Dreamer (1985), which was followed by the even more well-received Grimscribe: His Lives and Works (1991). Ligotti’s work has a small, but dedicated circle of fans, many of whom raised a whole lot of noise during the first season of True Detective (2014) when they accused show creator Nic Pizzolatto of ripping off Ligotti’s work. Specifically, fans accused the show of lifting entire passages from Ligotti’s short stories, as well as his philosophical book, The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (2010). When the evidence is examined and fully tabulated, it is hard not to see that Pizzolatto and others took Ligotti’s work and ran with it. In fact, Pizzolatto himself admitted in an interview that season one lead Rust Cohle (played by Matthew McConaughey) mouths Ligotti’s philosophy.

But what is Ligotti’s philosophy, and does it inform his weird fiction? First of all, Ligotti is a philosophical pessimist and anti-natalist (someone who is opposed to the further procreation of human beings). His stated influences are Emil Cioran, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Peter Wessel Zapffe. Cioran, often cited as the “Philosopher of Despair” or the “Philosopher of Failure,” began his life as a gifted Romanian student and follower of the Iron Guard movement before renouncing everything, moving to Paris, and writing morbid philosophy tracts during prolonged bouts of insomnia. Schopenhauer, the man most closely associated with pessimism, was a known curmudgeon who spent his life in academia and as a private scholar. As for Zapffe, the Norwegian philosopher penned an entire essay, 1933’s “The Last Messiah,” denouncing life as a grand error. Ligotti is a man who swims in these same waters, admitting that human consciousness is the greatest horror of them all. Thus, for him, life is either a matter of suicide or the preferable constant state of intoxication “by means of drugs and technology such that we will always exist in a state of good feeling and die without fear or pain.” As such, Ligotti is a democratic socialist who believes that the welfare state should make everyone as comfortable as possible “while they’re waiting to die.”

Ligotti’s fiction is rife with themes of pessimism and the pain of existence. Yet, as bleak as his philosophy is, Ligotti’s short stories are enjoyable. They are ornate and gothic yarns that move in a languid manner. They are the opposite of splatterpunk, and indeed Ligotti cannot be labeled as “pulp” in any meaningful way. (That is unless you consider all cult authors working within the weird fiction genre as pulp.) Much like Lovecraft, Ligotti is a writer and dreamer out-of-step with the larger trends in his genre.

Ligotti’s most Lovecraft-esque short story is also his most well-known work— “The Last Feast of the Harlequin.” First published in the April 1990 edition of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, “The Last Feast of the Harlequin” follows an unnamed social anthropologist with a special interest in clowns. The lonesome scholar journeys to the town of Mirocaw in the Midwest, where the “Fool’s Feast” is celebrated between December 19 and 21. The narrator not only wants to learn more about the feast, but also wants to locate the missing Professor Raymond Thoss, a fellow anthropologist who left behind notes indicating that the Fool’s Feast is connected to ancient pagan rites, notably the Roman Saturnalia, and various visions of worm-liked creatures found in Poe and the work of the Syrian Gnostics. The further the narrator goes into Mirocaw, such as discovering the town’s problem with seasonal suicides, the more he uncovers disquieting suggestions. Ultimately, while wearing motely himself, the narrator discovers that the Fool’s Feast is a cover for an eldritch ceremony of unnamable horror. “The Last Feast of the Harlequin” is a classic for obvious reasons. It exudes dread on almost every page, plus Ligotti is a rare weird fiction author who echoes Lovecraft without plagiarizing him or engaging with his cosmos. The world of “The Last Feast of the Harlequin” is a world of Ligotti’s own design that includes familiar Lovecraftian tropes (secret rites, academic protagonist, etc.) without any of the obvious stylistics.

Other notable stories by Ligotti included the corporate horror of “Our Temporary Supervisor,” where a Kafka-esque situation unfolds inside of the confines of the Quine Organization. “Dr. Voke and Mr. Veech” concerns love and the use of puppetry to get it. On the surface, “The Frolic,” one of Ligotti’s earliest tales, is a serial killer story. However, “The Frolic” takes that straightforward subject matter and complicates it in interesting ways. “Drink to Me Only with Labyrinthine Eyes” concerns a stage magician and his beautiful assistant who hide a horrific secret until it is discovered by an attendee at a private party. Ligotti’s lone attempt at a screenplay, entitled “Crampton,” proved too odd and pessimistic even for the X-Files.

Even in stories with familiar creatures, such as vampires, Ligotti manages to make things seem abnormal, strange, and thoroughly melancholic. It is the latter quality of pervasive sadness that makes Ligotti’s fiction unique. Whereas other horror writers often grapple with the primordial fear of death, Ligotti writes about the endless horror of life. His is a world of deep paranoia and pointlessness. Even his villains seem sad and pathetic, which they are as fellow sufferers of the world we all inhabit.

This brief introduction does little justice to the work of Thomas Ligotti. His is a pen that refuses to follow trends (Ligotti has never written a novel, and likely never will), and although not prolific, it has been a major voice in weird fiction for multiple decades now. In the deepest way, Ligotti is a true heir to Lovecraft, from his philosophy to his views on weird fiction. An original par excellence, Ligotti may not be our kind of pulp, but he’s our kind of writer—deeply inventive and unquestionably original. To read him is to swallow the obsidian pill.

10/10 article

dude sounds like bummer at parties