Owing to the enduring popularity of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, many of the New Pulpsters (my semi-official name for the new wave of dissident pulp scribes currently taking over the world) tend to have a Weird Tales-centric myopathy. Yes, it is without question that the magazine overseen by editors Edwin Baird and Farnsworth Wright was the most trailblazing publication during pulp’s golden years. Weird Tales not only published Lovecraft and Howard’s greatest and most enduring stories, but it also gave the world many excellent stories from writers so often neglected like Donald Wandrei, Carl Jacobi, Clark Ashton Smith, and others. As such, younger pulp writers often skip those magazines perceived as B-level and go straight for the top stuff.

This is a mistake, however. During pulp’s heyday between the world wars, several unique and invigorating magazines pumped out incredibly high quality content at a frenetic pace. Some of them were the standard-bearers in their respective genres, while others created and continued the mythology of all-American heroes. Here, in this small amuse-bouche, some of the best pulp magazines not named Weird Tales will be discussed and given the limelight for a change.

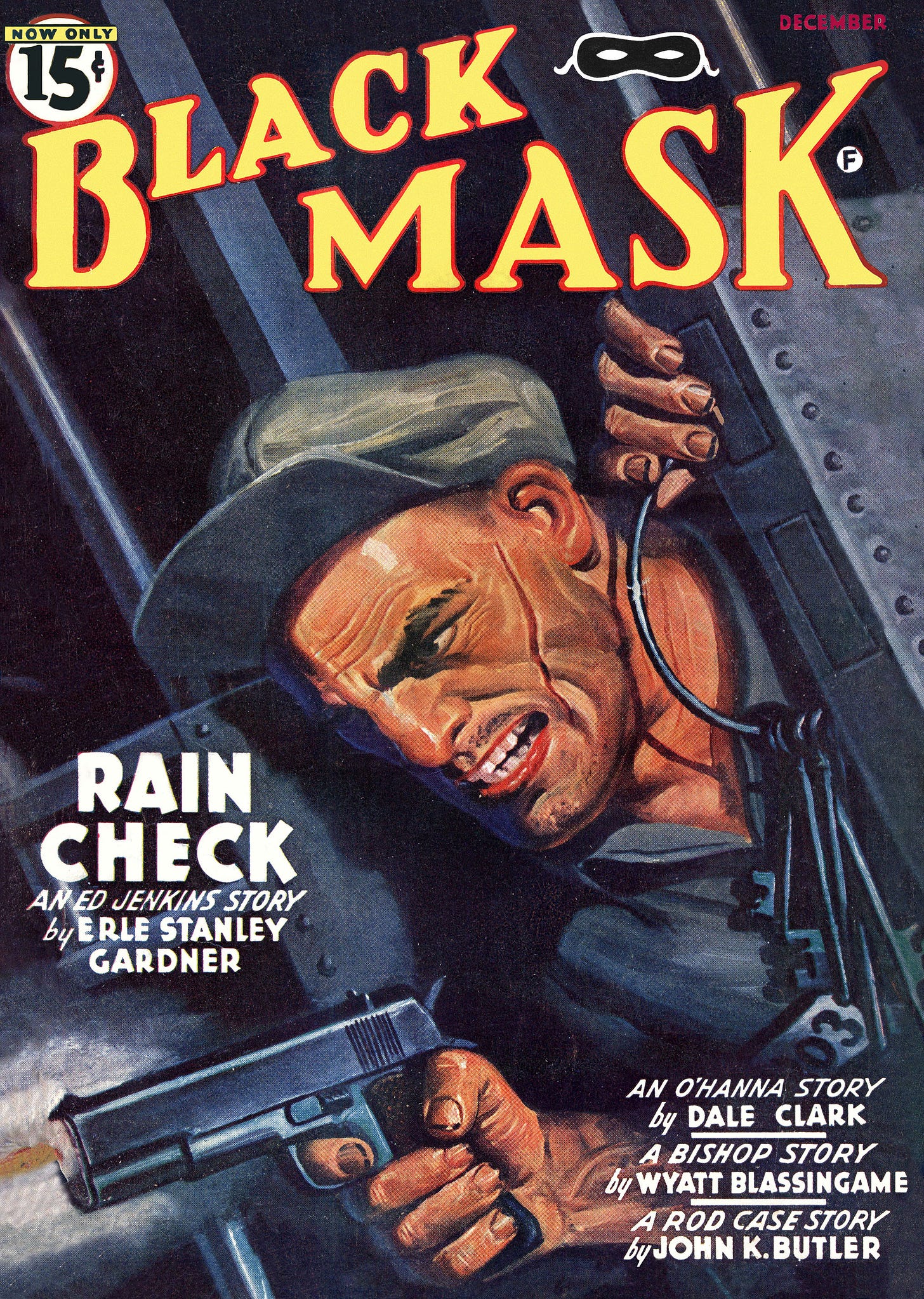

In his 1944 essay for The Atlantic Monthly entitled “The Simple Art of Murder,” detective novelist Raymond Chandler pontificated on the sharp differences between American and British crime fiction. Chandler, himself a transatlantic gentleman born in America, reared in Britain, and a veteran of the Canadian Army during World War I, articulated the notion that American crime fiction, unlike its older British counterpart, had a basis in reality. To Chandler’s view, American stories and novels dealt with crime as it exists, rather than its highly sanitized and intellectual ideal. Bodies in the library and eccentric sleuths were replaced by tough-talking gumshoes and bullet-riddled corpses on the streets. This literary revolution began in the pulps in the 1920s, and no pulp magazine better embodied this American “hardboiled” style of crime fiction than Black Mask.

Originally launched in April 1920 by conservative journalist H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan, Black Mask was intended to be the lucrative, mass market partner to the pair’s more highbrow Smart Set magazine. Mencken and Nathan recouped their initial $500 investment quickly and easily, and eventually they sold the magazine for $12,500 to publishers Eltinge Warner and Eugene Crow. The magazine would see the apex of its power after pulp adventure writer Joseph “Cap” Shaw was named editor in 1926.

Black Mask specialized in the new breed of tough crime and detective stories. It published what is considered the first modern private detective story with Carroll John Daly’s “Three Gun Terry” (May 15, 1923). Speaking of Daly, besides creating the earliest tough-as-nails P.I.s like Terry Mack and Race Williams, he is also the progenitor of the hardboiled genre, as his story “The False Burton Combs” more or less established the style in the December 1922 issue of Black Mask.

The writer most associated with Black Mask was none other than the great Dashiell Hammett, a former Pinkerton operative who turned his real world experiences into a series of stories and novels that are still consumed with gusto today. Chandler himself credited Hammett with inventing the hardboiled genre, and it was Black Mask who published Hammett’s first stories. Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason, also first saw publication in Black Mask. Ditto for Chandler, too. In essence, Black Mask is the origin point of hardboiled American detective fiction, which in turn means it is also the origin point for film noir.

Begun by Harry Steeger of Popular Publications in December 1932, Dime Mystery Magazine started out as just another crime publication. However, in October 1933, the magazine took a bold new direction. In that month, Dime Mystery Magazine became the primary distributor of “shudder” or “weird menace” pulp stories. Inspired by the Grand Guignol theater tradition of Paris as well as the then popular crime fiction of Edgar Wallace, the weird menace sub-genre delighted in scenes of torture (especially the torture of half-nude women), suggestions of supernatural evil, and the most outlandish forms of crime imaginable. Weird menace stories of the time were usually set in supposedly haunted houses or in secret underground laboratories. The villains were often costumed monstrosities who tried to mask their criminal activities as the workings of otherworldly creatures. In the end, the ruse is discovered and all the hoodoo is explained away as a series of tricks and technics. Capable writers such as Hugh B. Cave, Frederick C. Davis, and Wyatt Blassingame filled the magazine with such stories. A later contributor to the magazine was Ray Bradbury.

The creation and proliferation of the weird menace pulp style is the legacy of Dime Mystery Magazine. Hanna-Barbera made the genre family friendly in the 1960s, and thus the weird menace innovation entered the immortal halls of popular cultural memory.

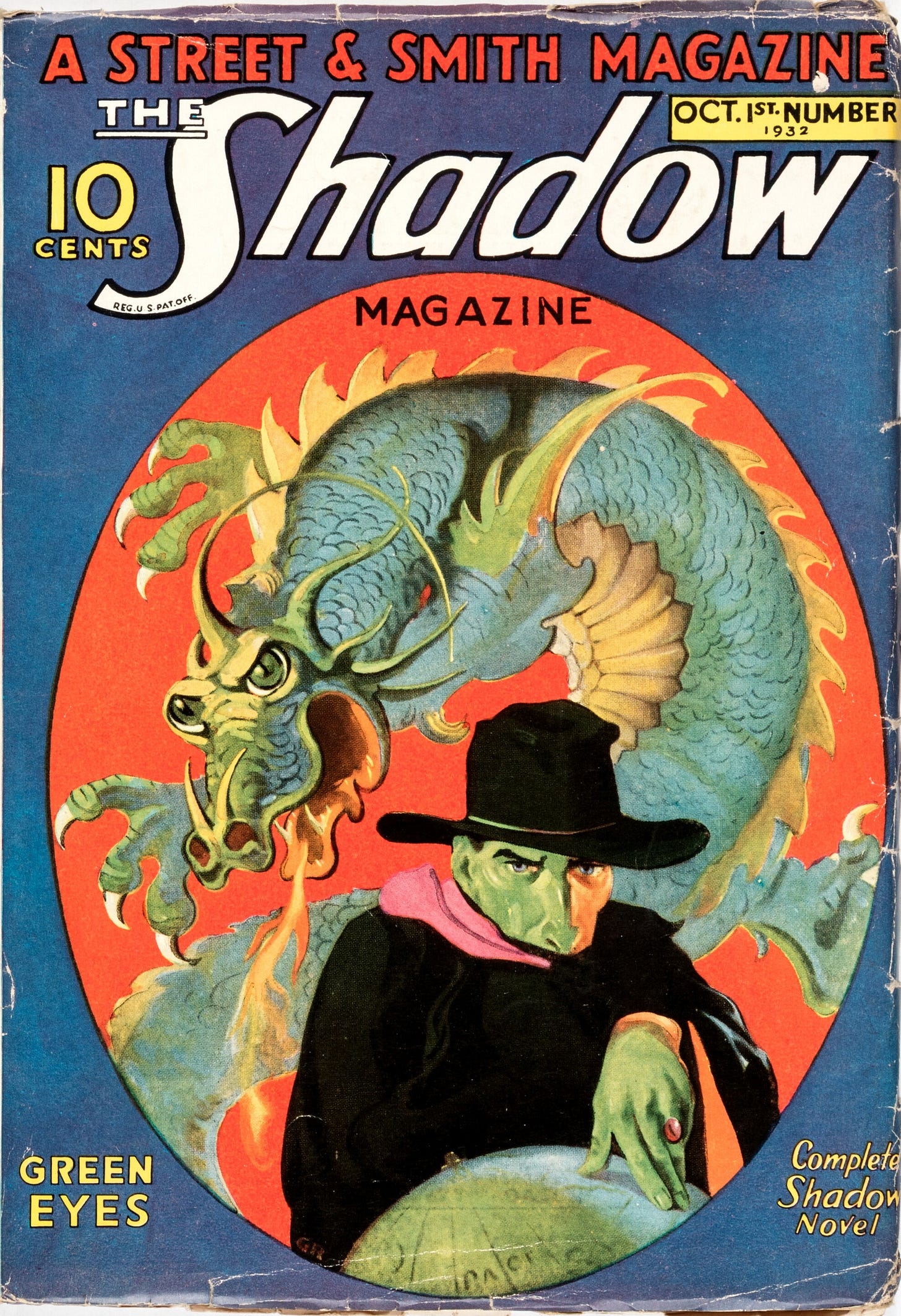

As a certain friend of the Bizarchives continues to show, no pulp was more profoundly influential than The Shadow. Launched in 1931 by Street & Smith as a monthly character pulp, The Shadow soon became a major sensation. To this day, The Shadow remains one of the best-selling and most popular characters ever created thanks to the radio show, films, and later, comic books. Using the in-house pen name of Maxwell Grant, author and stage magician Walter B. Gibson lent his incredible prose and storytelling abilities to the character, a wealthy playboy named Lamont Cranston who is in actuality a disfigured World War I flying ace and secret agent of Russian monarchists named Kent Allard.

The Shadow and his many agents would continue to hunt down mobsters and weird menace-like villains in the pulps until 1949. By that point, Gibson’s many novellas, plus the occasional short tale from the likes of Doc Savage creator Lester Dent, had already made The Shadow a household name. Today, most recognize The Shadow as the progenitor of Batman, one of contemporary cinema’s towering figures. The first series of comics featuring Batman are almost word-for-word, image-for-image knockoffs of The Shadow. This fact alone means that The Shadow magazine continues to be the most accessible and relevant pulp of our time. Imagine a world without Batman…

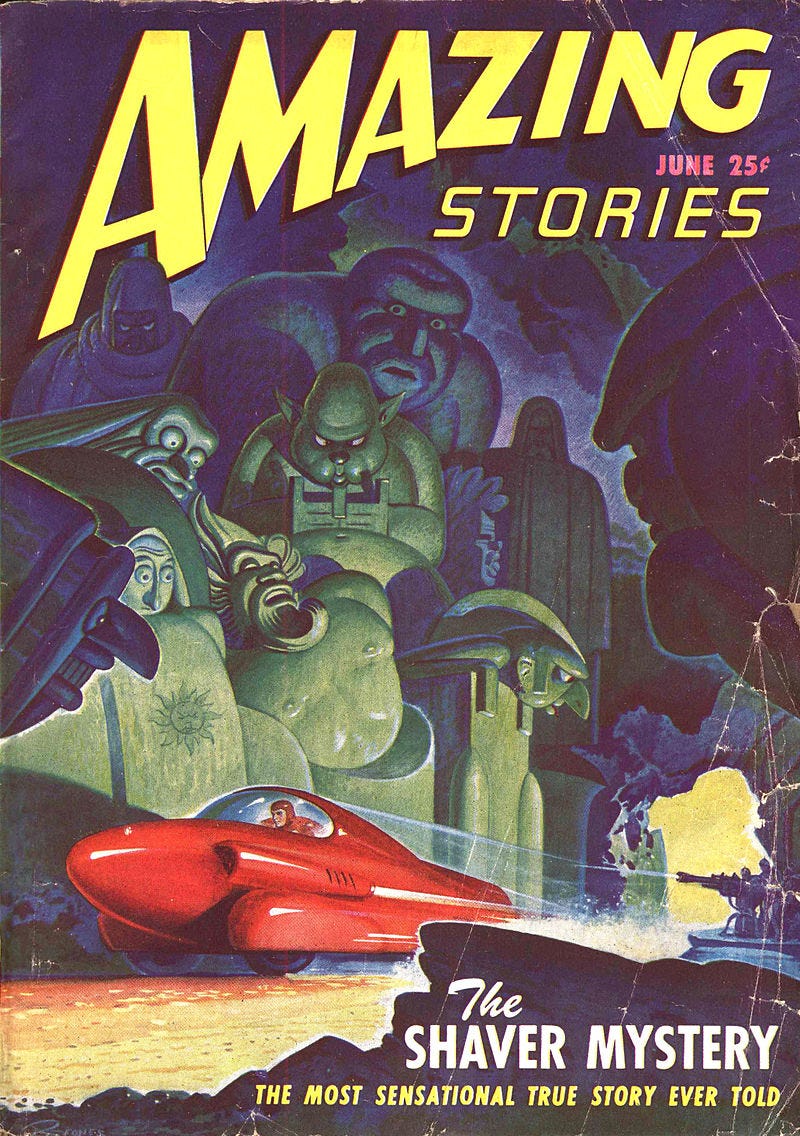

Science fiction as we know it began in the pulps. Specifically, the April 1926 debut of Amazing Stories is the moment when science fiction was born as a distinct genre. First published by the Luxembourg-born writer and inventor Hugo Gernsback, Amazing Stories paid tribute to the founders of science fiction by frequently republishing the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, and H.G. Wells. The magazine also fostered the incredible talents like Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Philp K. Dick, and Fritz Leiber. Under the leadership of owner John W. Campbell, Amazing Stories produced some of the finest fiction in the world during the 1930s, providing readers with early archetypes of the mad scientist, the cosmic explorer, and the future worlds now so beloved by sci-fi fans across the globe.

Unlike many of its competitors, Amazing Stories continued well into the 1950s and 1960s when other pulp magazines had gone belly-up. Indeed, the magazine would only cease publication in 2005 (!) after years under the ownership of Dungeons & Dragons legend Gary Gygax. No pulp magazine had anything comparable to the run of Amazing Stories, and only a select few can say that they too created an entire genre of popular fiction.

These pulps and many others helped to disseminate a distinctly American and working class take on literature and entertainment. Their influence is immense and only continues to grow as the current crop of mass entertainment remains underwhelming and captured by politics. You should go back and read these four publications and many others in order to find your own inspiration. The desiccated realm of literature desperately needs New Pulpsters, and new New Pulpsters can only be created by reading the classics. Well, these are the pulp classics. Read and share widely.