Pulp fiction is often thought of as a Western phenomenon. This is no mere prejudice; what we know of as pulp fiction began in the United States and was soon exported to Europe, primarily the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. However, pulp found an unlikely home in the Land of the Rising Sun. Beginning in the 1920s, Japanese magazines and journals began publishing translations of Western pulp works, with a special emphasis on detective tales. One of the key translators would become one of the key creators, and thus set the groundwork for an entirely native-born genre of pulp fiction.

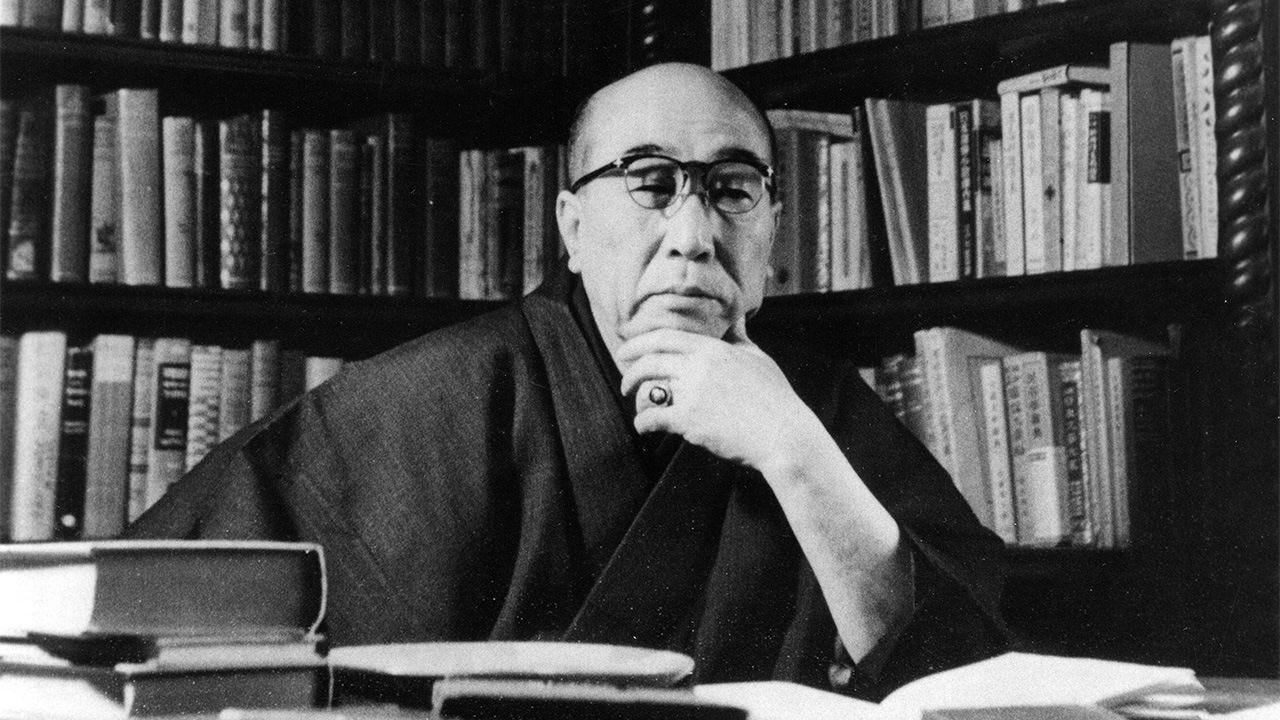

Tarō Hirai (平井 太郎, Hirai Tarō, October 21, 1894 – July 28, 1965) was born in the town of Nabari in the Mie Prefecture. Hirai came from aristocratic lineage. His grandfather belonged to the Tsu clan as a samurai. At the age of two, Hirai’s family moved to Kameyama. Young Hirai enjoyed a quality education growing up, and after being groomed for it, enrolled at the prestigious Waseda University in 1912. Hirai graduated with his undergraduate degree in economics four years later. Rather than pursue a stable, professional career, Hirai became something of an economic vagabond. He hustled at odd jobs ranging from a soba noddle hawker to a newspaper cartoonist. In 1923, after years of grinding in the publishing industry, Hirai found his calling as a fiction writer and translator.

His first published tale, “The Two-Sen Copper Coin,” is an exquisite mystery yarn about two impoverished men and a complex joke involving a neighborhood robbery. The story proved popular enough that Hirai began focusing his attention on crafting more mystery tales. Rather than write under his own name, Hirai adopted the pseudonym of Edogawa Ranpo (sometimes spelled as Edogawa Rampo). The name is a Japanese transliteration of Edgar Allan Poe, Hirai’s chief literary influence. As Edogawa Ranpo, Hirai spent decades, roughly from the mid-1920s until his passing in the mid-1960s, crafting and publishing unique pulp tales that blended several genres together, notably mystery, detective fiction, and horror.

Ranpo’s best-known story is “The Human Chair.” Originally published in a literary magazine in October 1925, “The Human Chair” is a psycho-sexual chiller that uses the now-rare epistolary format. Yoshiko is a popular short story writer who receives a strange and unexpected manuscript one day. The manuscript is unsigned and comes from an unknown male admirer of Yoshiko’s work. The manuscript details the man’s grotesque crime. Namely, the author of the manuscript admits to Yoshiko that he custom designed a Western-style chair for the purposes of living in it. To be more precise, the author, who claims to be a cabinet maker by trade and horribly disfigured, fashioned his human-sized chair so that he could enjoy the pleasure of being sat on by unseen women.

Most of the obscene manuscript discusses the author’s infatuation with a European woman who sat in his human chair whilst it was positioned in a hotel lobby. For Yoshiko, things take a dangerous turn when the author begins discussing a new love in his life—a beautiful, well-proportioned Japanese woman. Said woman is the wife of a diplomat and a writer. Yoshiko realizes that the woman in question is her, plus she looks with horror upon the new, large, Western-style chair in her home. The manuscript ends with a request for a face-to-face meeting between Yoshiko and the twisted chairmaker.

I will not spoil the surprise ending to “The Human Chair.” Suffice it to say that Ranpo’s most famous story is the perfect distillation of the many themes that reoccur time and time again in his fiction. Aberrant psychosis and sexual perversity often collide in Ranpo’s main characters, many of whom are liminal men existing at the margins of Japanese society. Another sterling example of this quality is the 1926 novella, The Strange Tale of Panorama Island. The novella follows the life of a down-and-out writer named Hitomi Hirosuke. Broke and aimlessly drifting, Hitomi only lives for his cherished dream of owning his own island and turning it into a playground for adults like him. Hitomi’s usual bad luck changes when Genzaburo Komoda, a wealthy industrialist and landowner who went to school with Hitomi, passes away. In life, Genzaburo was often indistinguishable from Hitomi. Strangers often mistook the pair for each other. Remembering this, Hitomi resolves to steal the dead man’s identity and fortune.

After completing a series of morbid tasks, including digging up the dead man’s body and inserting Genzaburo’s gold tooth in his mouth (after first ripping out his own tooth), Hitomi successfully becomes Komoda. Hitomi uses his false identity to purchase an island and begin construction on a gigantic pleasure palace. This island paradise includes mechanical wonders, airplanes, underwater tunnels, luscious foliage, classically inspired villas and statues, and a massive panorama detailing Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). The island has other pleasures as well, as Hitomi populates it with naked acrobats and actors, all of whom engage in open-air orgies and other sexual acts. But the sex that Hitomi is interested in is with the late Genzaburo’s wife, the lovely Chiyoko. She is the only one intimate enough with the confidence man to know his secret. Therefore, during a dazzling firework show, Hitomi secures his secret by strangling the beautiful woman and dumping her body into the pristine waters within the island’s amusement park.

Hitomi’s fever dream comes to an end thanks to an enterprising detective. Speaking of detectives, Ranpo’s greatest character is none other than the private investigator Kogoro Akechi. A young, university-educated genius who also a master of judo, Akechi is Ranpo’s Sherlock Holmes and his muse who appeared in countless short stories and novels. The detective even has a band of young helpers, the Boy Detectives Club, who are clearly modeled after Holmes’s own Baker Street Irregulars. But, given that he is the creation of the mad genius Ranpo, Akechi solves cases of a far more outré bent than Holmes. Akechi’s murders always contain either a whiff of the impossible (a locked room, for example) or supernatural. Akechi has his own Moriarity in the Fiend with Twenty Faces, except the Fiend bears a closer resemblance to the French super-villain Fantômas. The Fiend’s plots are always dastardly beyond measure, and usually threaten all of Japan. The Fiend is also a master chameleon whose filthy fingerprints are hard to trace. Hard, that is, unless you are the great Akechi…

Ranpo’s peak of creativity lasted until the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), when some of his stories were censored by the military government as being potentially harmful to morale. After 1941, when the Japanese Empire and Allies fought tooth-and-nail all across the Pacific, Ranpo busied himself by writing patriotic detective stories for children and serving as a civil defense volunteer. Once the war ended, Ranpo’s career took a different focus, as the author became a major editor and booster of detective fiction in Japan. Ranpo did more than anyone else to popularize Western detective fiction in Japan, which in turn lead to a postwar explosion in Japanese detective stories and novels, most of which mimicked the classical style best exemplified by British masters like Agatha Christie and Anglophilic Americans like John Dickson Carr. Nowadays, Japan is one of the major hubs of detective fiction in the world with its own idiosyncratic styles, some of which still echo back to Ranpo and his unusual fusion of East and West.

Ranpo passed away at age seventy after suffering many years with Parkinson’s and various heart ailments. This death merely ended his flesh. Ranpo’s titanic spirit lives on in Japanese fiction. Ranpo is especially popular among manga writers, with superstars and horror specialists Junji Ito and Suehiro Maruo adapting several of Ranpo’s classics. Many of these adaptations, as well as Ranpo’s originals, have been translated into multiple European languages. Thus the circle fully closes, as Ranpo began as a consumer and stylist in the Western mold, and today’s pulp fiction connoisseurs can consume and admire the uniquely Japanese style of Edogawa Ranpo. This is a good globalism. The only globalism that matters…

PULP IMPERIALISM.

Nice!

I’ve been hearing about him for years, but the only thing I knew was that his name is amazing and he wrote mysteries.

Thanks for that!