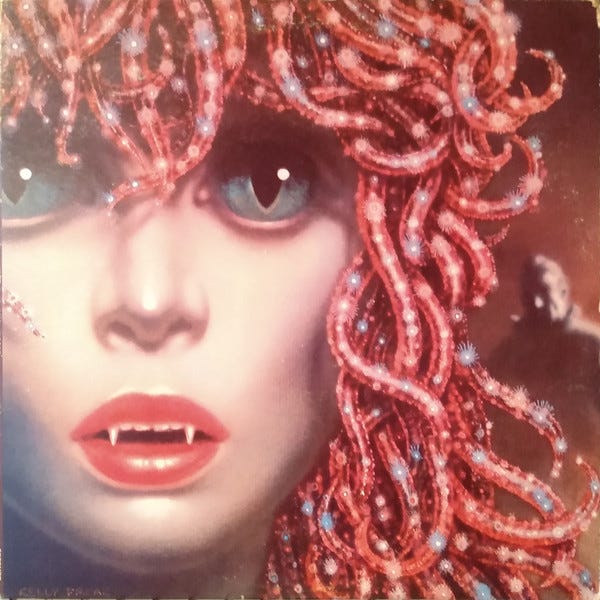

Shambleau

C. L. Moore's introduction to Science Fiction and the Weird

Catherine Lucille Moore’s Weird Tales stories proved to be foundational to many of the mainstays of pop science fiction and fantasy. Xena, Red Sonja and Red Sonya, Malcom Reynolds and Serenity, Han Solo, Chewbacca, and the Millennium Falcon. C. L. Moore was the first to put women in Sword & Sorcery, inspiring R. E. Howard and others to write tales of fiery red-heads who could match blades with Conan.

In science fiction, her tales of Northwest Smith, his partner Yarol, and their ship The Maid inspired many tales of smuggler in space. The first of these, and the first of all of C. L. Moore’s stories, is the haunting “Shambleau.”

The name itself is a warning cry, one Northwest Smith should have paid attention to. But when a crowd chases down a turbaned alien woman in rags, Smith’s nobler instincts kick in. He faces down the mob and declares himself as the girl’s protector—to the aghast horror of the crowd.

The young woman clings to her rescuer, and over the next couple days, Smith is captivated by her. But there is a struggle to find food suitable for the seductive little beauty. Until she removes her turban, revealing the nest of red serpents that make up her hair. Little Shambleau is part Gorgon, part Siren, and pure psychic predator. Even with her alienness revealed, her charms are powerful. And Northwest Smith’s resolve is crumbling, even as his dreams are haunted by nightmares.

Before the Shambleau can consume Northwest’s will, leaving Smith as a infatuated walking husk, Yarol bursts in, confronts the monster, and saves the day with a long pull from his raygun. And to his horror, Northwest Smith wonders if he wishes he should not have been saved.

C. L. Moore brings a velvety moodiness to this predatory romance that makes the simple horror of waking up next to a monster quiver. One that has to be read instead of merely discussed. And for a certain kind of romantic, the masterful control of mood makes the revelation of the Shambleau’s true nature a sucker punch as a man’s noblest instincts re used to try to destroy him. Contemporary Weird Tales was full of morality tales, where evil men following their vices introduce themselves to monsters. Here, the horror is heightened by a good man doing the right thing—only for his very goodness to be preyed upon. And the tale just purrs along without being crass enough to merit a place in those career-ending spicies.

Perhaps E. Hoffman Price’s reaction, found in The Book of The Dead, says it best:

"Read this!” [Farnsworth Wright] commanded…

I obeyed. The story commanded my attention. There was no escape. I forgot that I needed food and drink—I’d driven a long way…The stranger’s narrative prevailed, until, finally, I drew a deep breath, exhaled, flipped the last sheet to the back of the pack, and looked again at the by-line. Never heard of it before.

“For Christ’s sweet sake, who and what is this C. L. Moore?”

He wagged his head, gave me an I-told you-so grimace.

We declared C. L. Moore day. I’d met Northwest Smith and Shambleau.

Given how many times the unlucky Northwest Smith comes across doomed redheaded lovers in his following adventures, it may be that the redheaded Moore was trying on various feminine roles, from good girls, to dying beauties, to shrews, and seductresses. And without Yarol’s frequent help, these fiery sirens would pipe Smith to various horrific demises, often with a smile on his face. But that may be a misconception just as gross as many lingering around C. L. Moore parroted by Wikipedia and N. E. Reilly.

Catherine Lucille Moore did not go by her initials because she was female, but because she feared discovery of what would have been a side hustle by her employers. Besides, Weird Tales already had female regulars in the author pool, so a fervent WT reader like Moore would know that her sex was no barrier to publication in that magazine.

Additionally, “Shambleau” was not conceived as a space western as claimed by Reilly without sources. Although many tropes would be raided from Northwest Smith’s adventures, C. L. Moore, in her “Afterword: Footnote to ‘Shambleau…and Others’”, describes the birthing of “Shambleau.” She had steeped herself in Gothic poetry when the image of a helpless woman fleeing an almost medieval crowd came to mind. The rest of the characters fell into place by way of contrasts. Since science fiction’s inception as a separate genre in the 1920s and 1930s, its critics have had a tendency to reach back into the past and declare various predecessors as “science fiction” despite genre differences. Barry Malzberg and Isaac Asimov both noticed, bemoaned, and debunked claims made from this tendency. Again, space westerns borrowed liberally from Northwest Smith. That doesn’t make “Shambleau” a space western…

…or even science fiction at all.

Despite the futuristic setting, “Shambleau” differs from standard science fiction in one major respect. Whether the hard speculative fiction of Wells and Campbell or the hard science of Verne and Gernsback, science fiction has been built around the exploration of scientific rules, laws, and conjectures. These rules can postulate grand advances, as in the pyschohistory of Asimov’s Foundation, or chilling horrors, such as in Tom Godwin’s “The Cold Equations”. The actions, technology, and even the setting flow from these rules.

“Shambleau” is not about rules. “Shambleau”, as Yarol states within, “[talks] about things I cannot define—things that I’m not sure exist.” Things outside the rules, or even those that the rules say should not exist.

Things…a bit…

Weird.

Gothic, even.

Science fiction tells the reader how to survive according to the rules of nature. Gothic tells the reader how to survive when the rules of nature no longer apply. When the rules of polite society, like helping the helpless, no longer work the way they are supposed to.

When that innocent little waif turns out to be a drooling Gorgon—and you’re now on the menu.

If you survive, you’ll have one hell of a story to tell.

Just like Northwest Smith…

…and C. L. Moore.