“My ethics are my own. I’m not saying they’re good and I’m not admitting they’re bad, and what’s more I’m not interested in the opinions of others on that subject. When the time comes for some quick-drawing gunman to jump me over the hurdles I’ll ride to the Pearly Gates on my own ticket. It won’t be a pass written on the back of another man’s thoughts. I stand on my own legs and I’ll shoot it out with any gun in the city–any time, any place.”

The Snarl of the Beast (1927) by Carroll John Daly

Hardboiled fiction is a distinctly American innovation. Prior to the 1920s, detective fiction was genteel. Detective fiction was Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson examining the bodies of middle class men in London or the charming English countryside. Then, at the inauguration of the Jazz Age, Agatha Christie and her like penned wildly popular novels about eccentric amateurs solving complex puzzles built upon blood and tragedy. This is in no way meant to demean Dame Agatha or any of the cozy writers. This type of detective fiction has stood the test of time, and reminds popular today.

But it is not based in reality. Real criminals are red in tooth and claw. They swear, they have ignoble motivations, and most of the time they are simply dumb. The same can often be applied to the detectives who chase them. No one knew this better than Dashiell Hammett, a former Pinkerton agent whose final and most memorable case involved snooping on behalf of silent film comedia Fatty Arbuckle during one of his trials for sexual assault in San Francisco. Hammett brought the real ugliness of cops and criminals to the fictional page, turning the fledgling pulp magazine Black Mask into one of the most important publications in the history of American letters. The autodidact Hammett, who took to pulp writing as a way to supplement his income whilst battling tuberculosis, took detective fiction writing seriously, too. In a series of “rules” for aspiring detective fiction writers, Hammett stood in favor of realism over the fanciful:

There was an automatic revolver, the Webley-Fosbery, made in England some years ago. The ordinary automatic pistol, however, is not a revolver. A pistol, to be a revolver, must have something on it that revolves.

The Colt’s .45 automatic pistol has no chambers. The cartridges are put in a magazine.

A silencer may be attached to a revolver, but the effect will be altogether negligible. I have never seen a silencer used on an automatic pistol, but am told it would still make quite a bit of noise. “Silencer” is a rather optimistic name for this device which has generally fallen into disuse.

When a bullet from a Colt’s .45, or any firearm of approximately the same size and power, hits you, even if not in a fatal spot, it usually knocks you over. It is quite upsetting at any reasonable range.

A shot or stab wound is simply felt as a blow or push at first. It is some little time before any burning or other painful sensation begins.

When you are knocked unconscious you do not feel the blow that does it.

A wound made after death of the wounded is usually recognizable as such.

Fingerprints of any value to the police are seldom found on anybody’s skin.

The pupils of many drug addicts’ eyes are apparently normal.

It is impossible to see anything by the flash of an ordinary gun, though it is easy to imagine you have seen things.

Not nearly so much can be seen by moonlight as you imagine. This is especially true of colours.

All Federal snoopers are not members of the Secret Service. That branch is chiefly occupied with pursuing counterfeiters and guarding Presidents and prominent visitors to our shores.

A sheriff is a county officer who usually has no official connection with city, town or state police.

Federal prisoners convicted in Washington, D.C., are usually sent to the Atlanta prison and not to Leavenworth.

The California State prison at San Quentin is used for convicts serving first terms. Two-time losers are usually sent to Folsom.

Ventriloquists do not actually “throw” their voices and such doubtful illusions as they manage depend on their gestures. Nothing at all could be done by a ventriloquist standing behind his audience.

Even detectives who drop their final g’s should not be made to say “anythin'” an oddity that calls for vocal acrobatics.

“Youse” is the plural of “you”.

A trained detective shadowing a subject does not ordinarily leap from doorway to doorway and does not hide behind trees and poles. He knows no harm is done if the subject sees him now and then.

The current practice in most places in the United States is to make the coroner’s inquest an empty formality in which nothing much is brought out except that somebody has died.

Fingerprints are fragile affairs. Wrapping a pistol or other small object up in a handkerchief is much more likely to obliterate than to preserve any prints it may have.

When an automatic pistol is fired the empty cartridge shell flies out the right-hand side. The empty cartridge case remains in a revolver until ejected by hand.

A lawyer cannot impeach his own witness.

The length of time a corpse has been a corpse can be approximated by an experienced physician, but only approximated, and the longer it has been a corpse, the less accurate the approximation is likely to be.

Hammett’s striking realism, plus his razor-sharp and thoroughly Anglo-Saxon prose, is often believed to the be origin of the hardboiled genre. The popular belief is that Hammett’s short stories and novels created the uniquely American archetype of the lonely, tough, and violent private eye out to rid the world of lousy dames, underworld creeps, and corrupt politicians.

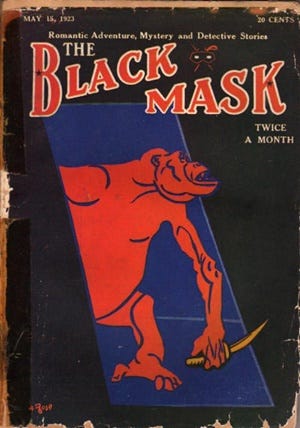

The people who think this are wrong, but not seriously wrong. The truth is that the first hardboiled story, “The False Burton Combs,” was published in Black Mask several months before Hammett’s first story ever saw print. The author of that story, Carroll John Daly, rarely gets the credit he deserves. Not only did Daly invent the hardboiled genre, but his rough, two-fisted writing remains just as relevant and influential as either Hammett or Chandler.

Carroll John Daly (1889-1958) wrote about tough guys, but he certainly did not look like one. Slender, with a trimmed mustache and owl-eyed spectacles, Daly grew up in Yonkers, New York. Educated at De la Salle Institute and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, Daly became a professional writer in the early 1920s. “The False Burton Combs” was one of his earliest tales, being published by Black Mask in December 1922. “The False Burton Combs” is a crime caper about a private eye who assumes the identity of a wealthy playboy during a Nantucket vacation. The story is not exactly what one expects when they hear “hardboiled,” but all the elements are there.

Daly excelled at creating characters. His first creation debuted in the April 1923 issue of Black Mask. Three Gun Terry Mack is the first of the fictional private eyes to have it all: a gruff way of speaking, a predilection for violence, and a bad case of femme fatale attraction. Terry Mack walks the mean streets of New York City with three guns on him at all times (hence the nickname). He is a brute and a bruiser. There is nothing subtle about him. He solves cases not via his “little grey cells” or mathematical deduction; Terry just beats the shit out of everyone.

Daly’s most influential character, Race Williams, debuted in Black Mask in June 1923. Another tough guy private eye from New York City, Williams’s first story was “Knights of the Open Palm.” This story appeared in a peculiar edition of Black Mask, as the entire issue was dedicated to one controversial subject—The Ku Klux Klan.

During the 1920s, the Klan reached the zenith of its popularity. Membership peaked at around one million, with many joining the so-called Invisible Empire because of its stated defense of Anglo-Protestant America and “dry” (see: pro-Prohibition) laws. The Klan of the 1920s was anti-immigrant, severely anti-Catholic, and often at the forefront of significant political legislation (public schooling in Oregon; creation of Leif Erikson Day in Maine). Black Mask opened up the editorial floodgates by asking its writers to pen pro- and anti-Klan stories for the issue. Daly’s yarn fell definitely in the anti-Klan camp, as “Knights of the Open Palm” critiques the Klan and other secret societies as being a hotbed of perverts and hypocrites out for nothing but personal gain. More importantly, Daly put into the mouth of Williams a contrasting view of Americanism at odds with the one promoted by the Klan— a worldview of hyper-individualism and disdain for group identity inspired by the multi-ethnic New York City that Daly lived and breathed in. Williams jokes that he is a “born joiner” like all Americans, and yet he rejects the calls to racial solidarity exemplified by the Klan-like group in the story.

Daly continued to crank out Race Williams stories and novels well into the 1940s. Mickey Spillane sent Daly a letter claiming that his writing, specifically his Race Williams stories, influenced him above all else. The connections are obvious: both Daly and Spillane were New Yorkers who wrote ballsy and violent stories about New York private eyes that were hated by the critics. Spillane’s Mike Hammer novels were eaten up like popcorn by Americans for decades, and yet the critics only ever had terrible things to say about Spillane (Ayn Rand being a notable exception). As for Daly, his own editor at Black Mask, “Cap” Joseph T. Shaw, hated with work with a passion. And yet, every time a Daly story appeared in Black Mask, sales jumped by fifteen-percent. Much like in Weird Tales, where Seabury Quinn’s Jules de Grandin stories usually won the day against the works of Lovecraft, Smith, and Howard, Black Mask readers almost always picked Daly over Hammett.

Daly and Hammett diverged in the 1930s. After finding success with The Maltese Falcon, Hammett moved to Hollywood to write scripts. He washed out. Hammett never wrote seriously again after the publication of his 1934 novel The Thin Man. He became an ardent communist who served time in jail for violations of the Smith Act. Congressional investigations and disillusionment took hold, and Hammett died as a hermit in Manhattan in 1961.

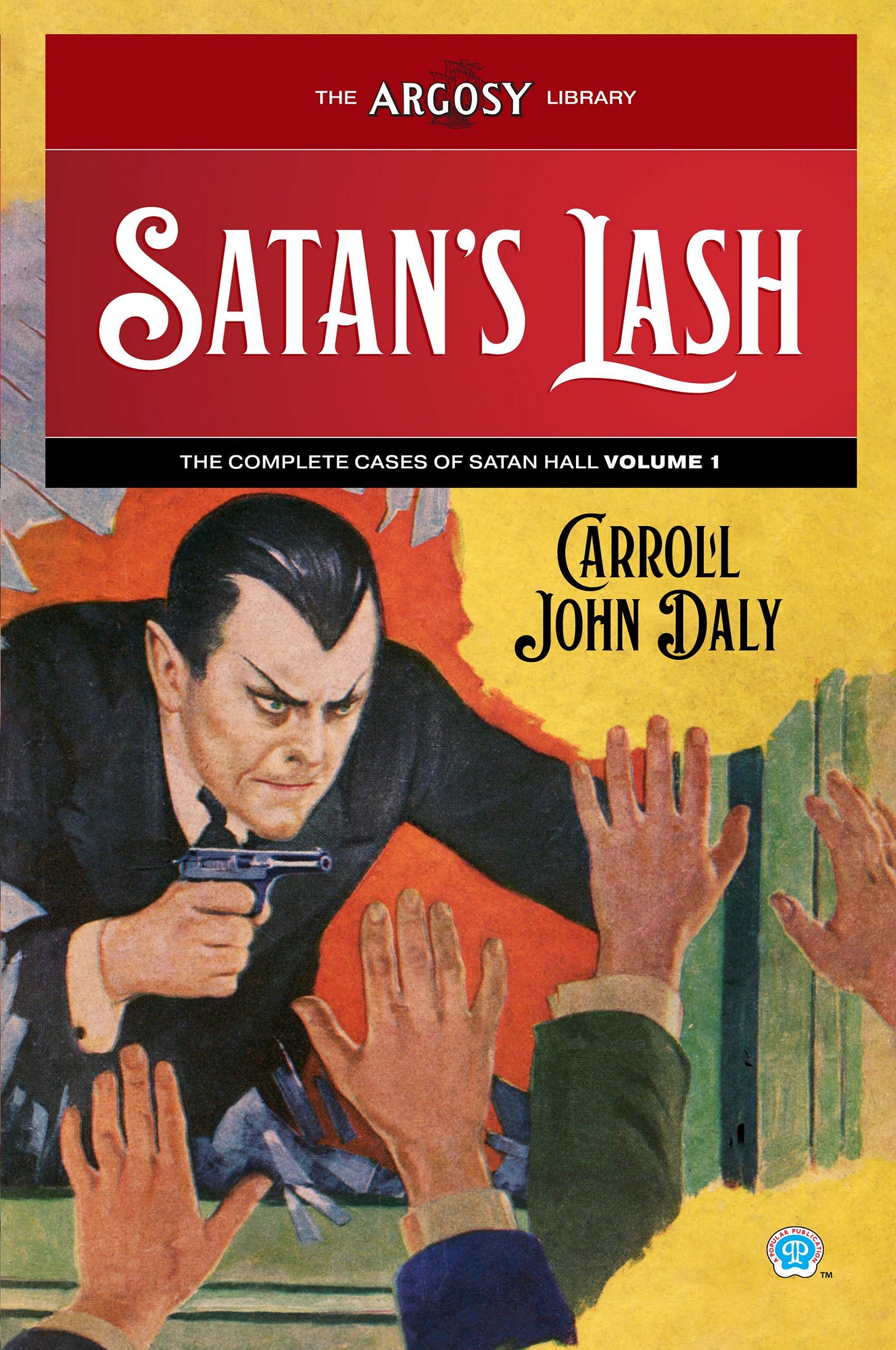

Daly, on the other hand, never ceased writing. In 1931, Daly took his talents to Detective Story Magazine, where he created the NYPD detective Frank “Satan” Hall. Satan Hall not only looks like the Devil, but he acts devilish too. Indeed, Satan Hall’s favorite gambit is to coax the crooks into shooting first so he can justifiably kill them. That is Satan Hall’s M.O. When the pulps started to dry up in the 1940s, Daly moved to Los Angeles to write for the movies and comic books. He also pumped out a slew of novels, with sixteen published between 1926 and 1951. Like Hammett, Daly died in January, but three years earlier in 1958.

Daly has long existed in the shadow of Hammett. The truth is that Daly not only invented hardboiled, but his fiction had a much bigger impact on pulp writing than Hammett. Hammett was the first pulp writer to be praised by the high-brow set, while Daly created legions of imitations, most notably in the masked avenger pulps featuring The Shadow, The Spider, and The Phantom Detective. Without Daly, American popular fiction would be a much more anemic thing. For that alone, the man deserves praise. No old commie need apply.

Excellent article. Thank you for the very useful point by point list as well...!