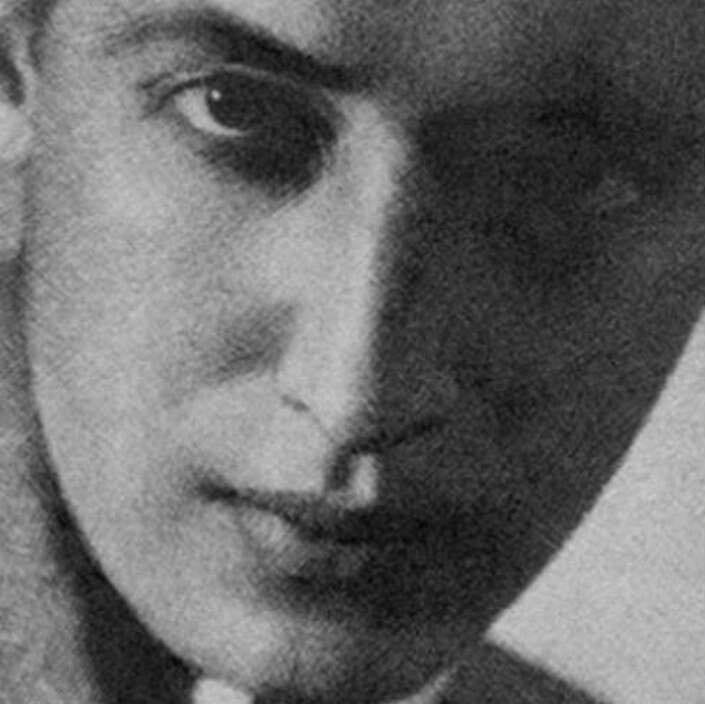

Frederick Nebel lived a life as hardboiled as any of his characters. Born in 1903, Nebel spent his early years in New York City. There, the Staten Island native tried his hand at a variety of tough jobs like stevedore, dock hand, and seaman aboard a tramp steamer. Later, Nebel turned land-lover in Canada, working as a farm hand in the frozen north until he decided to do something a little more intellectual. Since it was the 1920s, the halcyon age of the pulp magazines, Nebel, a high school drop-out, started writing stories.

Nebel would go on to dedicate multiple decades to pulp writing. His three typewriters supposedly churned out four million words over twenty-five years. And Nebel wrote more than stories, too. He also committed novels, novelettes, and nonfiction articles to paper. Like many of his contemporaries, Nebel was more craftsman than artist. He earned his daily bread through quantity, not necessarily quality. Nebel did not take himself too seriously, either. Around the time that he called it quits in the 1950s, Nebel made a point of turning down editors whenever they sought to publish collections of his pulp tales. As far as Nebel was concerned, his work had served its purpose, leaving them alone in the original issues was good enough.

Given this mentality and given the fact that Nebel’s name is virtually unknown today, one could come to the conclusion that the dude was a hack. Maybe a hack’s hack (and thus a cut above the truly abhorrent scribblers), but a hack nonetheless. One could think this, but one would be wrong.

During his peak, Nebel was one of the premiere writers at Black Mask, the magazine most closely associated with hardboiled detective fiction and noir. When Hammett quit the pulps for good in 1930, Black Mask editor Joseph Shaw tapped Nebel to fill the legendary wordsmith’s shoes. That is how highly Shaw regarded Nebel’s work. (Shaw not only considered Nebel a fantastic writer, but the famous editor also considered him more important to the genre than Carroll John Daly, the inventor of hardboiled.)

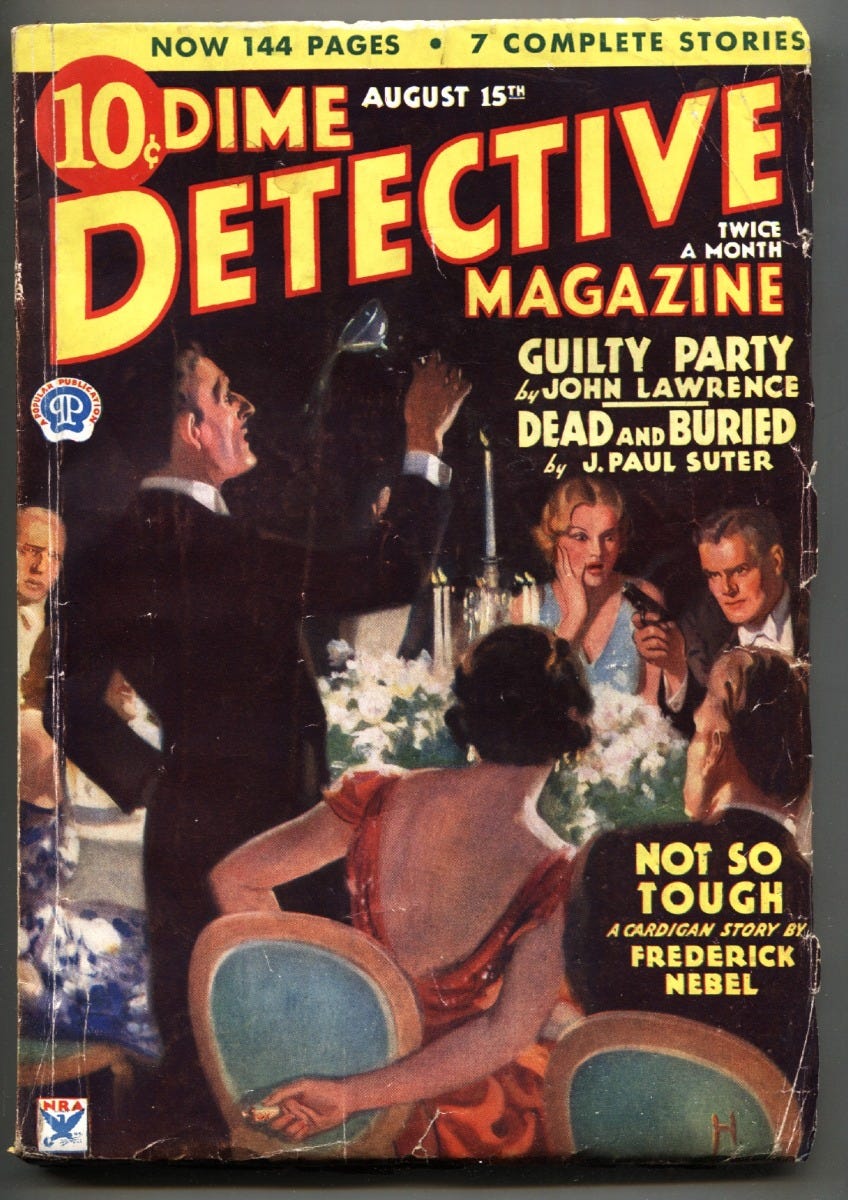

In an odd twist of fate, Nebel’s best work and most immortal character appeared in Dime Detective Magazine, one of the chief rivals of Black Mask. Nebel’s Jack Cardigan first appeared in the November 1931 issue of Dime Detective. That first story, “Death Alley,” sets out all of the relevant information about the character: Cardigan is a private investigator with the Cosmos Agency, he is big, tall, and strong, has shaggy hair that is always getting into his eyes, and he is a grumpy Irishman prone to fighting with the police and crooks alike. The first handful of Cardigan stories take place in St. Louis, where Cardigan mostly squares off against corrupt politicians and their lackeys on the city police force. Although someone usually dies in the Cardigan stories, murder is rarely the central crime. In “Hell’s Pay Check” (December 1931), a state senator hires Cardigan to retrieve the damning evidence of that could tie the senator’s son to not only a “loose woman,” but also a gang of blackmailers. In “Six Diamonds and Dick” (January 1932), Cardigan has to shake down jewel thieves with dangerous connections to the political machine in charge of St. Louis.

Later, during the run of Cardigan stories that appeared in Dime Detective in 1932, Cardigan not only relocates to New York, but he also gets a partner in the form of Pat Seaward. Pat is short for Patricia, and this female P.I. proves to be just as tough and resourceful (and far more charming) than Cardigan. Again, these Cardigan and Seaward tales usually involve theft and blackmail, such as “The Candy Killer” (November 1932), which features a Pola Negri stand-in kidnapped by a gang of xenophobic dope-fiends.

All told, Cardigan appeared in Dime Detective forty-four times between 1931 and 1937. Cardigan’s cases often left New York, but they rarely left the country. A private dick as rude as Cardigan would not have done well in polite Toronto or genteel London. Cardigan’s gruffness, plus the sheer velocity of Nebel’s writing, make these tales ultra-hardboiled. Yes, they are so true to the genre that they are stereotypical. Every character speaks like a tough guy, and every female (minus Pat) is up to no good. Everyone in Cardigan’s world is streetwise, but none are as savvy as him.

The Cardigan tales tend to be longer than the average pulp detective story, with most coming close to thirty pages in total. However, they feel short. The Cardigan tales prioritize action, verbs, violence, and dialogue. Sometimes they move so fast that it can be hard to keep up, and even harder to remember everything when it is all over. The one thing that cannot be forgotten is Cardigan’s unique form of saying Sayonara. “Goom-bye.” That’s what Cardigan says. Even when other characters in the story say “goodbye,” Cardigan gives them a goom-bye. It is never explained. It is Cardigan’s quirk, and his quirk alone.

While not particularly innovative, Nebel’s Cardigan stories are excellent examples of top-tier pulp writing. Furthermore, fans of hardboiled detective fiction can find a lot to love in them. There are four volumes of Cardigan tales currently for sale courtesy of Altus Press. They are the perfect place to begin and end, for they contain every single Cardigan story ever written. So, if you want the Long Goom-Bye instead of Chandler’s more famous (and slightly more effete) version, then give ole Jack Cardigan a chance.