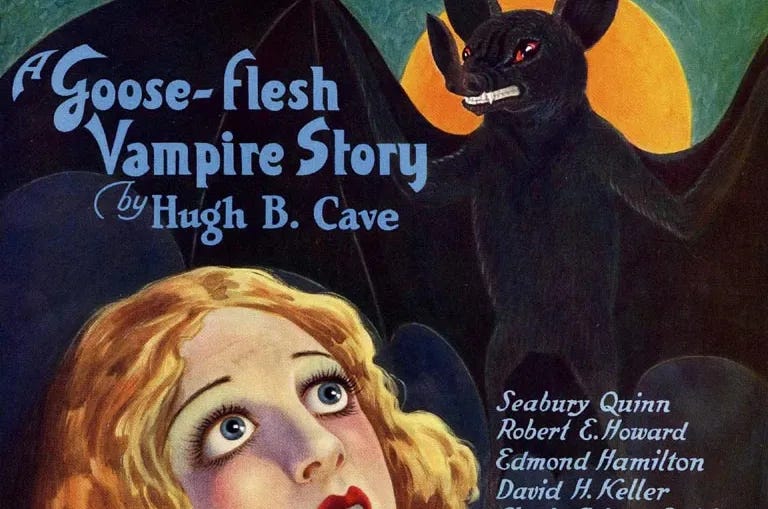

Hugh Barnett Cave (1910-2004) is most likely the greatest and most prolific pulp writer that you have never heard of, let alone read. Throughout his career, which spanned an incredible seven decades, Cave penned a whopping 1,000-plus short stories and 40 novels (plus much more non-fiction). Cave’s oeuvre included horror fiction, crime and detective fiction, adventure tales, and science fiction. This work appeared in some of the more notable pulp magazines of the interwar period, such as Weird Tales, Astounding Stories, and Black Mask. And yet, despite all of these accomplishments, Cave’s name rarely comes up when today’s pulpsters engage in chit-chat or respond to hellthreads on Telegram. That should be rectified.

Cave was born in Chester, an ancient cathedral town in northwestern England with Roman roots. The Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) brought his parents together, and the First World War caused them to leave England together. As a result, Cave grew up in the United States, specifically in the tony Boston suburb of Brookline. Cave attended the prestigious Brookline High School and gained entrance to Boston University. Unfortunately for Cave, he left BU after two years in order to support his family following a serious injury sustained by his father.

Cave’s first job was with a vanity press in Boston. It was while working in this unfulfilling position that Cave began penning his own stories. He sold his first professional story, “Island Ordeal,” in October 1929. Cave was just 19 at the time. Cave quickly became a mainstay of the pulp writing world, penning and publishing stories in an astounding array of magazines. On top of standalone tales, Cave created several serial characters. His two most popular were the hardboiled detective Peter Kane and the roving scamp known only as the Eel. The Kane stories appeared in Black Mask alongside the genre-defining work of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. In these action-oriented stories, Kane of the Beacon Detective Agency often gets involved in “weird menace” stories that contain more than a mere whiff of the supernatural. Cave was a master of the weird menace genre, and as such his Kane tales are perfect mashups of weird menace and noir fiction. As for the Eel tales, which Cave wrote under the goofy pseudonym of Justin Case, they appeared in Spicy Mystery Stories, a magazine that trafficked so much in nude women and salacious scenes that it can be described as softcore pornography. (Don’t judge Cave too much for this; Robert E. Howard published several “spicy” stories, too.)

Cave’s best-known stories are his handful of horror yarns published during the 1930s. One, “The Brotherhood of Blood,” was the cover story of the May 1932 edition of Weird Tales. “The Brotherhood of Blood” is a first-person vampire tale about a young man named Paul Munn. Munn falls in love with a beautiful young woman named Margot Vernee, who perishes suddenly on her twenty-eighth birthday after falling under a vampire’s spell. The vampire Margot promises to come for Munn when he turns twenty-eight, so, one of Margot’s failed suitors, Dr. Rojer Threng, locks Munn up in a university hospital. Threng has ulterior motives, and although he uses an electric crucifix and sunlight to vanquish Margot, he lets Munn become one of the undead. The story ends with Munn swearing vengeance against Threng for his deceit.

Another Cave cover story, “Stragella” is one of the author’s most anthologized tales. Published in the June 1932 edition of Strange Tales, “Stragella” concerns two sailors, Yancy and Miggs, who seek shelter aboard a strange vessel covered in growing vines. One night, another unknown ship appears from the mist, which causes a pair of bats to fly away in its direction. The bats are commanded by a Serbian vampire named Stragella, who attempts to turn Yancy into a fiend like her. A Bible in Yancy’s belt saves him from the vampire’s curse, but neither Yancy nor Miggs can stop the Night of Resurrection, where all the ship’s ghosts come alive again as slaves of Stragella and two other vampires.

At the same time as Cave was enjoying his most productive period, he began corresponding with other pulp writers. His longest friend and pen pal was the Minneapolis author Carl Richard Jacobi, the Weird Tales veteran best known for his vampire story “Revelations in Black.” The pair exchanged letters and other correspondence from 1932 until Jacobi’s death in 1997. These exchanges were friendly and warm. The same could not be said for Cave’s many letters with a fellow New England pulp writer — H.P. Lovecraft. For a time, Cave lived in Pawtuxet (now Crantson), Rhode Island. However, despite being less than an hour away from Providence, Cave never met Lovecraft. Instead, the pair traded fiery letters back and forth where the two writers debated the ethics of writing for the pulp magazines. None of these letters survive, unfortunately. But, given that Cave wrote at least two short stories set within Lovecraft’s cosmic horror universe, “The Death Watch” and “Isle of Dark Magic,” it is fair to say that the Old Gentleman from Providence had an influence on him.

During World War II, Cave stopped writing pulp tales and began writing war reports. As a war correspondent, Cave spent most of his time in the Pacific Theater, specifically Southeast Asia. Like fellow Englishman and pulp writer Ian Fleming, Cave learned to love the Caribbean during the war. He spent five years in Haiti before buying a coffee plantation in Jamaica. Cave returned to fiction writing during this period. Now that the pulps were going belly up, Cave began writing for the “slicks” like Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post. He also took up the novel, with a handful published in the 1950s. During this period of Cave’s output, stories about voodoo and Caribbean black magic predominated.

Things turned sour in the 1970s when the government of Jamaica confiscated Cave’s plantation. This forced Cave to relocate to Florida, where he was also reduced to selling his work to romance and women’s magazines. Cave did find an unlikely savior in the 1970s by the name of Karl Edward Wagner, who republished some of Cave’s 1930s stories in a volume entitled Murgunstrumm and Others (1977). This collection won the 1978 World Fantasy Award, thus granting Cave a new spark of creativity. Cave published several horror and fantasy novels during the 1980s and 1990s, and even published two novels in the 2000s. By the time of his death, Cave was not only a well-respected member of several horror and fantasy associations, but he was also a vocal champion of e-books who happily put most of his work online for free.

When it comes to pure pulp fiction, Hugh B. Cave is the prince of them all. All of his stories contain the type of action, intrigue, and economy of words that pulp fans love. While Cave was not a great innovator like Lovecraft or Clark Ashton Smith, and although he did not create immortal characters like Robert E. Howard, Cave deserves to be celebrated for his legendary productivity and the quality of his tales. Every Cave story is worth your time, as he was a master of atmosphere and dialogue. It was writers like him who created the unique pulp culture that we at the Bizarchives are trying to revive today, and for that we are eternally grateful to Mr. Cave.

thank you again for introducing me to yet another great writer!