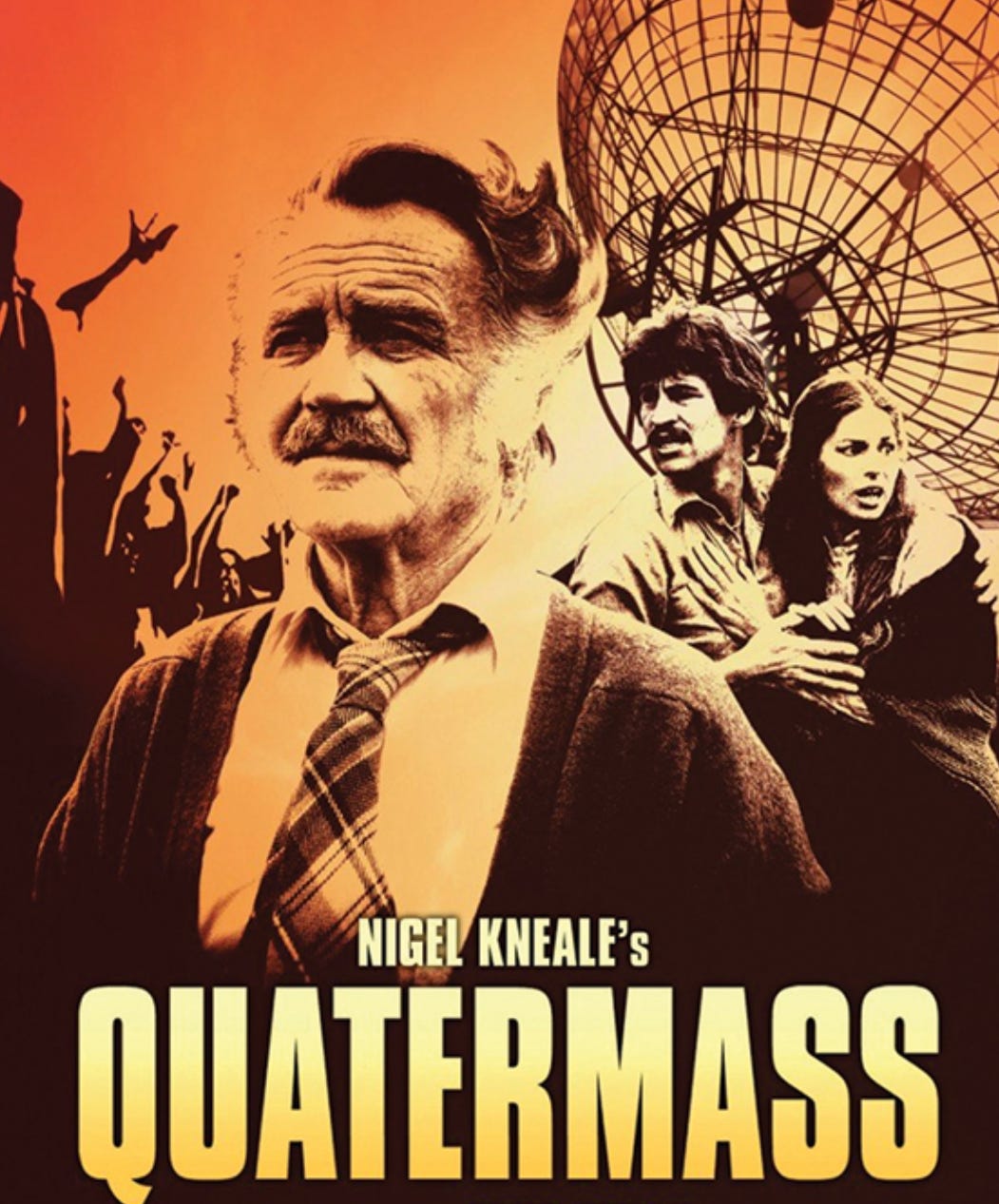

The Sting of Cosmic Horror: Quatermass 1979

“In the last quarter of the 20th century, the whole world seemed to sicken. Civilised institutions, whether old or new, fell ... as if some primal disorder was reasserting itself. And men asked themselves, ‘Why should this be?’”

— Opening narration, Quatermass, 1979

In April, I wrote a short piece here on The Obelisk discussing the golden age of British TV horror (Creeping Horror on the Box) where I mentioned the pivotal role played by a writer named Nigel Kneale. Recently, another of Kneale’s works, a 1979 four-part television serial entitled simply Quatermass, was forcefully brought to my mind when I was sitting out in my summer office (the garden). Having decided to take a five-minute break from writing, I kicked off my shoes, took off my reading glasses, stretched, and walked out onto the lawn. I drank in a deep draught of fresh country air, savoured the sweetness of the birdsong, and marvelled at the carpet of wildflowers that lay sprinkled across the grass like varicoloured floral stars. Several yards into this myopic, barefooted stroll, convincing myself that I was recharging my batteries by being suitably ‘earthed’, I was brought up short by a sharp, burning pain on the instep of my right foot.

A wasp sting.

Thus had Nature rewarded my efforts to draw a little closer.

But the needling of that small insect had immediately resurrected in my memory Kneale’s 1979 serial Quatermass.

A sting…

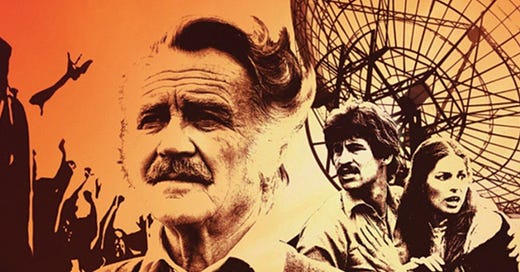

The eponymous lead character, Professor Bernard Quatermass, was originally created by Kneale in 1953 for the cosmic-horror television serial The Quatermass Experiment. Its success led to two sequels, Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass and the Pit (1958). These were seminal 1950s ‘science meets horror’ British television productions and Kneale went on to produce many scripts for cinema and television. Certainly, Kneale played a significant role in putting ‘the frighteners’ on British television audiences throughout the 1960s and 1970s, with the high points being his series Beasts (1976) and the inimitable The Stone Tape (1972).

Following the success of The Stone Tape, the BBC commissioned Kneale to write a ‘Quatermass sequel’, based in a dystopian but not-too-distant future. The serial was announced as a forthcoming four-part production and filming began in June 1973. However, budgetary problems and the unavailability of Stonehenge, a central location in Kneale’s concept, led to the project's cancellation. Kneale himself felt the BBC did not like the script: “didn't suit their image at that time; it was too gloomy”. Quatermass was, Kneale stated, “... a story of the future – but perhaps only a few years from now. There are some clues already in the most obvious places: the streets. Pavements littered with rubbish. Walls painted with angry graffiti. Worst of all, the mindless violence.” The project remained quiescent until 1977 when it was picked up by Euston Films, a subsidiary of Thames Television, with the intention of making the four-part serial as well as a film for cinematic release.

The plot is focussed on the arrival from deep space of an alien presence that begins to harvest mankind. Cultists roam across the countryside like deranged eco-warrior hippies, chanting and single-mindedly flocking to psychic beacons that lie beneath the earth, buried, supposedly, in some ancient period when the entity had visited to feast before. These ‘Planet People’ mass together on ancient sites thinking they are going to be lifted into an interstellar Nirvana when in fact they are merely an item on the menu.

After a futile and ultimately deadly joint Soviet and US effort to communicate with the entity using spacecraft, Quatermass is forced into action. He is, at first, an unwilling hero. His sole concern is to find his missing granddaughter who has become one of the Planet People ‘cultists’. But he cannot avoid this battle. And this is a conflict that requires not only a dogged determination but also a brilliant mind. Quatermass becomes absorbed by the challenge even with the realisation that it is simply impossible to destroy the threat. Undaunted, he conceives of a plan to touch it, to detonate a nuclear device right within its ‘reaper’ beam. This will, as he declares, “Sting it. Send a shock through its ganglia. It’ll be like a man who stepped on a hornet...”

“It’ll be like a man who stepped on a hornet...” that was the very line I had remembered following my encounter with the wasp. For, like an unmindful denizen of Cosmic Horror, I too had lumbered across the ‘universe’ (of my garden), ignorant of the countless thousands of garden critters that lay beneath my feet. I was on my own mission, the effect of my perambulations on the tinier lifeforms below of no conscious concern until, irritated by this Brobdingnagian interloper, the wasp struck back. Its sting was minor, but enough to send me off in the other direction cursing.

Although not critically well received at the time, the 1979 Quatermass is certainly a good yarn, well directed and produced, and with a strong ensemble cast. Thematically the series is dystopic in its depiction of a collapsing civilisation – the image of a strife-torn, almost post-apocalyptic London, is chillingly prescient. In addition, John Mills (Quatermass) was a fine actor and supported by Simon MacCorkindale (who had previously appeared in the episode ‘Baby’ in Kneale’s horror series Beasts), the two attempt to prevent the literal vaporisation of the planet’s youth.

I saw it when it first aired on British TV in the autumn of 1979. As a teenager, I was gripped by its depiction of a bleak dystopian future, convinced by the determined, brilliant scientist, and recognised the all-too-familiar, threat of global annihilation. The post-war era had morphed into a time of existential crises, oil shortages, overpopulation, a coming Ice Age, and imminent nuclear war... But, of course, these crises have been updated decade by decade, the ice age became global warming, then climate change, and, more recently, a pandemic. Perhaps, we are overdue an alien invasion…

Re-watching Quatermass nearly forty-five years later, it has weathered the years well. It is a convincing hybridisation of Cosmic Horror with Folk Horror, with a seemingly omnipotent yet indifferent alien entity pitted against a weak, degenerate society. But despite the odds, the hero endures, though he walks in the wintertime of civilisation. He must navigate between the rotting carcass of the urban to the mystery of ancient stone circles, he must face off against both psychotic roaming hippies and brutal inner-city guerrillas. Most of all he must conceive of a means to save what remains of humanity, a humanity that he, at least, still believes is redeemable and worth saving. Quatermass strides on to the very end, always searching for his lost granddaughter, and always striving, ever striving, to do the right thing against all the odds. He knows he cannot overcome the thing, any more than he can single-handedly rebuild society. But he can be the wasp, the gadfly, the hornet. If he can do that, that one small thing, then there might be a chance. Sometimes, one tiny sting is enough to move even the most belligerent ogre right along.