The literary legacy of H.P. Lovecraft is well known and often studied. The Cthulhu Mythos, Cosmicism, weird fiction. All of these permutations of Lovecraft’s original oeuvre remain solidly entrenched in horror fiction, both dissident and mainstream, all across the world. Anytime the word “eldritch” appears in print, or whenever something cephalopodic terrorizes a wayward town, that represents a lingering trace of the Old Gentleman from Providence.

Less appreciated are the more human connections that Lovecraft made during his brief life. The man mistakenly remembered as a shut-in and loner actually traveled widely and maintained a large list of correspondences. The inveterate letter writer swapped compliments, theories, opinions, and sundry with writers as respected as Robert Bloch, Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Fritz Leiber, and Henry Kuttner. Lovecraft had IRL friends too—the so-called KALEM Club met weekly while Lovecraft lived in the Big Apple. Here, men as distinguished as author Frank Belknap Long and critic Samuel Loveman spent nickels and dimes on coffee and sandwiches while talking and walking the night away alongside the famous “recluse.”

Later, after Lovecraft returned to his beloved Providence, several writers inspired by his work took it upon themselves to send him letters or request his vigorous editorial services. One writer, Donald Wandrei, took things a step further: Wandrei hitchhiked from his native Minnesota to Rhode Island in 1927 just to meet his favorite author. Lovecraft returned the favor by taking the Midwesterner on a grand antiquarian tour of Rhode Island and Massachusetts. All of this was of course capped off with a lavish ice cream party in Warren, Rhode Island.

Wandrei was born in Saint Paul on April 20, 1908 (thus making him almost eighteen years young than Lovecraft!). Wandrei came from an old pioneer family with literary connections. His father, Albert, worked for a publishing company that produced a large portion of America’s law textbooks at the time. For the majority of his life, Wandrei would continue to reside at his childhood home located at 1152 Portland Street in Saint Paul, and for him, Saint Paul was analogous to Lovecraft’s Providence.

To be fair, there was definitely something in the water of the Twin Cities during the Jazz Age. Saint Paul’s most famous son, F. Scott Fitzgerald, famously composed the epoch’s defining testament in The Great Gatsby. Elsewhere, two University of Minnesota students, Wandrei and Carl Jacobi, penned silly tales for Ski-U-Mah (the campus humor magazine) and more serious fare for the Minnesota Quarterly Magazine. Wandrei graduated from Minnesota with a B.A. in English in 1928, and like Jacobi (also an English graduate, class of 1930), decided to stick around the Twin Cities and make a name for himself as a pulp writer.

One of Wandrei’s first tales, “The Red Brain,” which appeared in the October 1927 issue of Weird Tales, was originally written when Wandrei was a sixteen-year-old high school student. “The Red Brain” is a horror-sci-fi yarn that details the horrors of a strange cosmic dust that envelops the entire world. From here, Wandrei would ply his hand at other gruesome tales, such as “The Shadow of a Nightmare” and “The Chuckler.” (The latter tale presents a kind of sequel to Lovecraft’s “The Statement of Randolph Carter.”) Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Wandrei’s short fiction regularly appeared in Weird Tales, Astounding Stories, and other pulp publications. Wandrei was a noted poet, as well, publishing an entire book of verse in 1928 entitled Ecstasy & Other Poems. (Wandrei also played the benefactor to another poet, Clark Ashton Smith, with Wandrei sometimes giving the Californian money.) Several more poetry volumes would follow, and much like his fiction, Wandrei’s verses tend towards the abnormal, disquiet, and discomforting. “Dream-Horror,” for instance, describes the utter dread of being buried alive.

They know that it will take me years to die,

Although my flesh with many knives is slit.

They would not burn me quickly on their spit;

How much more exquisite to hear me cry

With only rotten corpses lying by,

And bloated carrion rats that near me sit!

Beginning in 1933, Wandrei moved to New York City and took a job in advertising. At the same time, he continued to publish his own work and inspire others to contribute to the growing corpus of weird literature. Wandrei, who rumor states personally intervened in order to get Farnsworth Wright to publish “The Call of Cthulhu,” also branched out into crime and noir pulps like Black Mask. His detective character, I.V. Frost, first began solving high-tech mysteries in the pages of Clues Detective Stories in September 1934. Wandrei even managed to break out of the pulp ghetto and get some of his work published in Esquire—the slickest of the slick magazines.

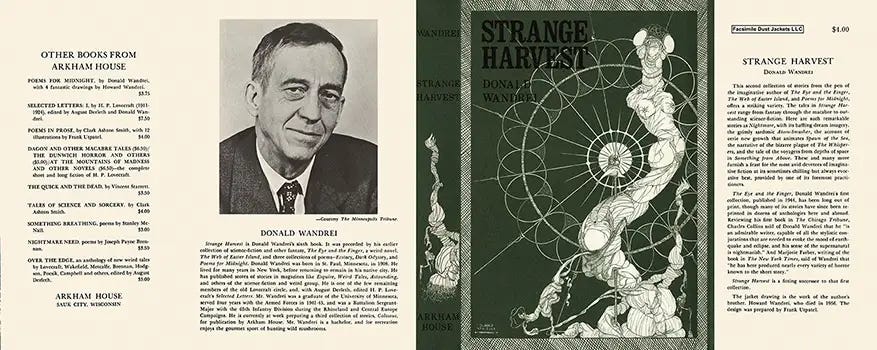

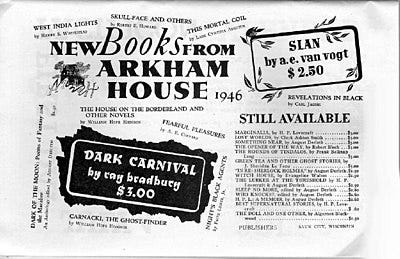

However, despite all of his publishing success, including the publication of a full-length novel, Wandrei’s most lasting legacy is Arkham House, a publishing imprint that he co-founded with August Derleth in 1939. Intended as a way to keep Lovecraft’s work in print, Arkham House would become one of the premiere publishers of weird and speculative fiction for over thirty years. Wandrei and Derleth’s offspring would not only save Lovecraft’s many stories from out-of-print Perdition, but it also published new work from Bloch, Jacobi, and younger talents like Ray Bradbury, Ramsey Campbell, and Brian Lumley. Of the two, Wandrei primarily focused on editing and compiling Lovecraft’s stories and letters into books, while Derleth did his part in cultivating talent, old and new.

During the Second World War, Wandrei served for four years as a technical sergeant in the 259th Infantry of the U.S. Army’s 65th Infantry Division. Given that Wandrei’s unit was part of General George Patton’s legendary Third Army, the writer saw heavy combat in Western and Central Europe until the Third Army reached Austria. The war seemingly sucked a lot of enthusiasm out of Wandrei, for he spent the majority of his post-war years either editing Lovecraft’s many letters or publishing the occasional book of poetry consisting of his work from the 1930s. Beginning in 1970, Wandrei brought suit against Derleth and Arkham House but ultimately returned as an editor following Derleth’s untimely death in 1971. While Wandrei’s productivity declined, his venom increased. Until his death in 1987, the elderly Wandrei made a small name for himself as a notable critic of sci-fi literature and speculative fiction fandom more generally. He famously declined to accept the World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1984 because he thought the award itself (a bust of H.P. Lovecraft) was an insulting and demeaning caricature of his old friend.

Of all of Lovecraft’s friends, pen-pals, and admirers, Wandrei is among the lesser known. The problem with this of course is that Wandrei was a writer of immense talent who left behind immaculate horror and mystery tales, along with hundreds of exquisitely gothic poems. One cannot claim the mantle of weird fiction enthusiast without first having read something from Wandrei. The man from Saint Paul may not have been the same caliber of stylist as Lovecraft, but his oeuvre is larger and more varied befitting of his skills as a true pulp maestro. Here’s a raised glass and three cheers for Donald Wandrei—the last of the Golden Age.

A very nice biography- he was a talented writer in his own right who needs more exposure.

Excellent and informative article. I need to read more of Wandrei's works now!